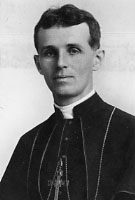

Bishop James E. Walsh, MM

Born: April 30, 1891

Ordained: December 7, 1915

Died: July 29, 1981

Maryknoll’s beloved Bishop James E. Walsh died peacefully at Maryknoll, New York, on July 29th. Completing sixty-six years as a priest and fifty-four as a bishop, he celebrated his ninetieth birthday on April 30th of this year. Since his release from the Shanghai prison eleven years ago, Bishop Walsh resided at the main seminary. His days were quiet and orderly with his prayers and Mass, his readings and frequent strolls. The evening of his life was one of personal dignity: the priest, the gentleman, a bother to no one, an inspiration to all.

Above all, Bishop Walsh was the dedicated missioner, deep of faith, full of humor, independent of manner. Perhaps he will be remembered mostly by others as the Bishop who spent twelve years in a Chinese prison. He will, however, be remembered more by Maryknollers as the Bishop who never uttered an unkind word about his captors. “The highest dream that can stir the heart of man is to squander it in the Charity of Christ for the souls of brother men.”

James E. Walsh was born the second of nine children, to Mary Concannon and William E. Walsh, in Cumberland, Md. on April 30, 1891. James Edward’s humor and writing ability developed early. His father sent him off to parochial school when he and his brother bedeviled their teacher by “reciting our lessons standing on our heads”. After being graduated from Mt. St. Mary’s College at age 19, James worked two years as timekeeper in a steel mill where “the world as a sort of fairyland came to something like its true light. Finally I found that when I surrendered myself to the thought of the priesthood a sort of holy joy filled my soul.” Both his mother and father were overjoyed at his decision to be a missionary priest. “As soon as I read the title ‘American Catholic Foreign Mission Seminary’ I felt at once that this was what I had been waiting for.”

James entered the first class of Maryknoll in 1912 and on December 7, 1915 became the second priest ordained in the Society. Three years later he was assigned to China. That first remarkable mission group consisted of Fathers Frederick Price, Francis X. Ford, Bernard Meyer, and James Walsh. They departed for Kwong Tung, China, on September 8, 1918. A year later, after the death of Fr. Price, Fr. Walsh became the Superior of the Maryknoll Mission in China. Pope Pius XI named Father Walsh, at age 36, as the first bishop of the Vicariate of Kongmoon. The missioner, to whom the Chinese Catholics gave the name of Wha Lee Son (Pillar of Truth), was ordained Shepherd of the Church on May 22, 1927, on Sancian Island, the death place of St. Francis Xavier. “The task of a missioner,” Bishop Walsh said at the time, “is to go to a place where he is not wanted, but needed and to remain until he is not needed but wanted.” Of his new role of Bishop he said to his missioners: “I am the least among you. Look upon me as your servant. I am made bishop chiefly to help you. If my help takes the form of direction, I hope you will realize it is intended to help just the same. But I think we understand each other; we are a happy family.”

Bishop Walsh returned to Maryknoll, N.Y. in 1936, following the death of Bishop James Anthony Walsh. In April of that year he was elected the second Superior General of Maryknoll. During his ten-year term he supervised Maryknoll’s first mission efforts to Latin America and Africa. At the Vatican’s request after his term of office, Bishop Walsh returned to China in 1948 as head of the Catholic Central Bureau in Shanghai to coordinate the Church’s missionary efforts throughout the country.

When the Communists came to power in 1949, all foreign clergy were harassed and pressured to leave. The government ordered Bishop Walsh’s Bureau closed in 1951. When Maryknoll superiors expressed concern for his safety, Bishop Walsh betrayed a trace of his Irish temper: “To put up with a little inconvenience at my age is nothing. Besides, I am a little sick and tired of being pushed around on account of my religion.” He was arrested October 18, 1958 and sentenced to 20 years in prison. During those years in jail he received no news reports and only one non-Chinese visitor. His brother, the late William C. Walsh, former Maryland State Attorney General, was allowed to visit him in 1960. Without advance notice he was freed from Shanghai’s prison hospital after serving almost twelve years of his sentence. Clad in rumpled khaki trousers and a faded checkered shirt, he walked across Hong Kong’s Lo Wu Bridge to freedom on July 10, 1970.

On his return to the States Bishop Walsh stopped in Rome where he was received in an emotional audience by Pope Paul VI. The Pontiff told the veteran missioner: “You have been a witness, authentic and simple, in joy and in sorrow, then in suffering and humiliation, and finally in separation from the people you loved so much. For all of this we thank you on behalf of the entire Church of Christ.”

On Monday, August 3, a funeral Mass was celebrated in St. Patrick’s Cathedral with H. E. Terence Cardinal Cooke as Principal Celebrant and Msgr. William McCormack, National Director of the Society for the Propagation of the Faith, as Homilist. Vespers and Wake services were conducted that evening by Fr. Robert Sheridan at Maryknoll. On Tuesday, the 4th, at Maryknoll’s Funeral Mass, Cardinal Cooke again celebrated and Fr. James Noonan was Homilist. Biography was read by Bro. Justin Joyce. Fr. Winslow led graveside service in the Maryknoll Cemetery.

A prolific writer, Bishop Walsh wrote six books including the popular “Man on Joss Stick Alley”, and a score of articles on mission life and work. His touching “clodhopper” story, Shine on Farmer Boy, appeared in the July, 1980, issue of Maryknoll magazine.

Perhaps, more than any other writing, the latter not only sums up the life of Bishop Walsh, whose motto in China was “Suffer the little children to come unto me,” but best expresses the deep, abiding vocation of Maryknoll: “I choose you, sang in my heart as I looked at my awkward farmer boy, perfect picture of the underprivileged soul, the overlooked and the overworked, the forgotten and despised…Shine on farmer boy, symbol to me of the thousand million like you who drew the Son of God from heaven to smooth and bless your weary anxieties and puzzled brows. I choose you and dedicate myself to you and I ask no other privilege but to devote the energies of my soul to such as you… Shine on farmer boy.”