When one thinks of mission work, the idea of helping individuals and groups of people throughout the world comes to mind. But what happens when your specialty isn’t humans, but animals? What does mission work look like for someone who cares for animals? As I asked myself this question, I found a Maryknoll Magazine article from November 1986 about former Maryknoll lay missioner Peter Johnson, aptly referred to as Maryknoll’s vet. Please read that very article below, as it provides a snapshot into how Peter was able to adapt his skills to help the communities where he worked.

Lay missioner-veterinarian from the Bronx serves Aymara peoples by helping them care for animals

Dr. Peter Johnson’s patients aren’t impressed with his barnside manner. Llamas spit, cows kick, chickens peck. But the Aymara people of Peru’s altiplano appreciate the skills of Maryknoll’s only veterinarian even if his patients don’t.

After arriving in Juli in 1984, the 29-year-old lay missioner participated in a program initiated by Maryknoll Sister Aurelia Atencio to rid cattle, sheep, llamas and alpacas of parasites. That project introduced Johnson to the people who till their fields and herd their animals on the shores of Lake Titicaca. He saw the need for a program that could be

maintained by Peruvians. ‘I wanted to start something that would stay in place after I leave, but I wasn’t sure how,’ he says.

The answer to Johnson’s quandary came when a group trained to provide basic health care to humans asked him to teach them about animal health. They were interested in becoming veterinary technicians who would use their knowledge to serve their communities. Encouraged by their enthusiasm and by the availability of locally produced teaching materials, Johnson developed a series of courses to train the technicians in the rudiments of preventing, diagnosing and treating ailments of local animals.

The missioner recalls the day he was driving along the mountain road in the gathering dusk when a lamb darted in front of the jeep as its 5-year-old shepherdess watched in horror. Over 30 stitches, penicillin and a splint fashioned from a wooden ruler took care of severed tendons and deep lacerations and helped dry the tears of the lamb’s young caretaker.

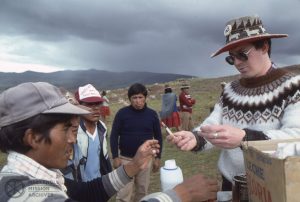

The first week-long series of classes Johnson gave to the veterinary technicians taught the basics of worming techniques. Later courses focused on diagnostic skills, administration of medication and the correct preparation of dips used to prevent hair loss due to parasitic infestations.

Johnson is impressed with his students’ eagerness to learn. ‘With each course they ask for more,’ explains the unassuming missioner.

He tries to satisfy that need while emphasizing the value of simple remedies and inexpensive, locally available products. For instance, when teaching the importance of maintaining a clean animal corral, Johnson urges the Aymara to use powdered lime, available in the local market for five cents per application rather than commercially prepared chemicals which cost $40 per application. Clean corrals, he says, prevent pneumonia and infections as well as hoof and mouth disease.

322 page “Manual Pecuario Para Los Promotores de Pecuaria” (Livestock manual for livestock promoters) written by Dr. Peter Johnson in Peru, 1986

The response of the Peruvian farmers to the courses has been gratifying to Johnson who admits to having been ‘a little nervous’ at first that he wouldn’t have many students. In April, 43 participants completed the fifth course of the program by attending six days of classes that combined classroom teaching with practical experience including administering hog cholera vaccine to unappreciative pigs.

Johnson anticipates that the Peruvian Ministry of Agriculture will soon recognize the graduates of his program as official veterinary technicians, giving them such privileges as the right to purchase vaccines through the Ministry.

The technicians’ course gives information to be used in service to the community. Johnson teaches similar but less complicated classes to individuals who wish to learn more about their own animals. Whole communities, including women and children, crowd into adobe huts to listen to Johnson’s lectures and watch videotapes played on a television powered by a car battery.

Early risers, the Aymaras would prefer to start classes at 4 a.m. but Johnson waits until dawn so he can see to write on the blackboard. ‘They always laugh when I draw a cow,’ he admits.

César Chahúares explains the cycle of parasitic infection in sheep to Aymara farmers in Peru’s altiplano.

Peruvian farms seem a surprising place to find a native of the bustling city streets of the Bronx, N.Y. His specialty in dairy cattle adds to the incongruous picture. But Johnson says it was natural for him to develop a love for farm animals after spending childhood summers on his grandparents’ dairy farm in upstate New York. Emphasis placed on farm animals by his alma mater, the Cornell University School of Veterinary Medicine, reinforced his interest.

Johnson recognizes that working with animals is an excellent way for a missioner to see God in people. He recalls the special inspiration provided by Andrés, a veterinary technician, who wears leg braces. A victim of polio, he arrived at Johnson’s courses every day riding a burro and he completed successfully all the field practice.

The Aymara people touch Johnson deeply. ‘I can only that God for the privilege of being with them,’ he says. ‘Nothing compares to the joy of being personally touched by God’s struggling and suffering children.’

Johnson loves the Aymara Indians who invite him into their lives by inviting him into their corrals.”

Maryknoll Magazine, November 1986, p. 47-49

By sharing his knowledge, Peter helped communities learn to care for their own animals, which are so important to their everyday existence and survival. Through the manual he created and these courses, the knowledge and skills he passed on enabled the communities he touched to continue to thrive long after Peter left his mission work in Peru. While Peter’s specialty was caring for animals, so many different gifts are possessed by all of us. It’s interesting to think in what ways we can utilize the gifts we have been given to help others. In this season of giving, take a moment to give a little of yourself to help others. That moment, big or small, can make a world of difference in someone’s life.

Wishing you all a happy holiday season!