As spring starts its roll into the summer months, we begin to spend more time outside. Undoubtedly, you have most likely seen some busy bees flying around while enjoying the outdoors. June happens to be one of the busiest times of year for bee colonies. They will soon be reaching their maxium colony populations for the year and are hard at work. I often see busy bees on the move while walking around the Maryknoll campus and wondered if a little bit of their history with Maryknoll had been recorded. After following some leads and digging through The Field Afar, I was able to find a few articles that capture a bit of their history at Maryknoll, beginning in September of 1917.

“Honey-Gathering.

The latest addition to the rapidly growing Maryknoll community is 100,000 bees, which came by auto from Mount Saint Alphonsus. These four-winged helpers promise to act as our unpaid fertilizing agents, to make wax for our chapel candles, and to give us a valuable substitute for sugar during these war times.

The queen runs the new community. She lays about a thousand eggs a day and seems satisfied, while others are satisfied to let her and her colony alone. Everybody works at Mayrknoll, even in the hives, for the workers have ejected the drones.

Since the workers and queen are all ‘lady-bees,’ the Teresians are happy. But not always. The other night, the telephone bell rang about five-thirty. At the convent-end of the wire an excited voice said: ‘Have Brother Bee come over immediately with his ‘bird cage’ and gloves – his bees have swarmed our community room.’

The brother found that the screen door had been left ajar, and half a hundred bold bad bees were buzzing around. Needless to say, the blue and the gray of the Teresian garb were very much in evidence – by their absence. The spiritual reading was held elsewhere.”

The Field Afar, September 1917, p. 140

Five years later, they decided to check on the progress that the busy bees had made on the Maryknoll Campus…

“How busy is a bee? Investigations are under way here. One of our men from Missouri slipped off with the truck, one day in early spring, and, when he came back, we owned an odd million of honey makers – twenty hives, each averaging fifty thousand occupants. Immediately, a Bee Culture Squad was added to the student manual labor departments, and, like true philosophers, to see to the bottom of the bee problems, a hive with glass sides was constructed.

Honey? The bee experts so promise us. A good hive averages one hundred pounds of eatable product a year (each pound, if you do not know, valued at fifty cents). Some fine day in some future fall, therefore, we shall inform you that we have a ton of honey gathered for the Maryknolls everywhere. Perhaps the news will be an enticement to you to run up and ask us to let you try our – bread.”

The Field Afar, June 1923, p. 179-180

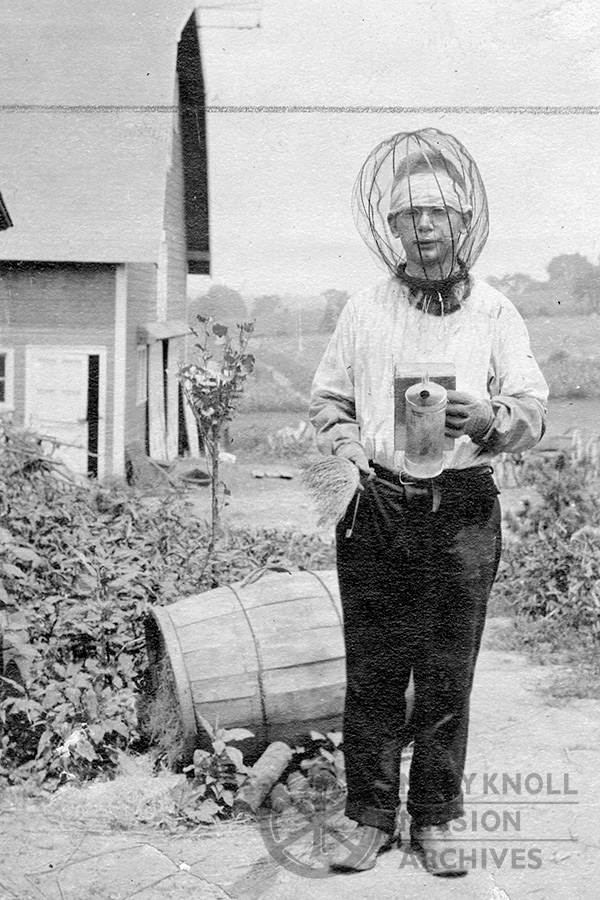

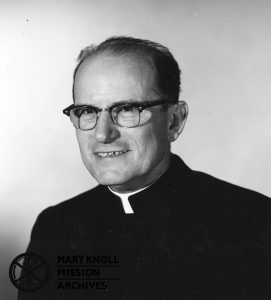

The back of one of the beekeeping images led to another article in the 1945 March issue of The Field Afar. It talks of an apiary (collection of hives), that was created in China by Fr. Constantine Burns during war time.

“Bees in our Bonnet

During these lean years in China, many a missioner has had to fall back on the skimpy knowledge of gardening, poultry, and pig raising that he picked up during the manual-labor period at the Seminary in his student days. Some of the missioners are doing very well for themselves. Father Constantine Burns, in particular, has raised vegetables and had, at one time, his own milk cows. […]He also had a successful apiary. Some of our students at the Seminary have followed his example and have gone in for this hazardous occupation. At home or abroad, it take an intrepid soul to handle bees.”

The Field Afar, March 1945, p. 34

Reading this snippet from The Field Afar made me wonder if there was more information about Fr. Constantine’s apiary. I went into the stacks to see if I could find any other mention of it in articles written by or about him. It was in the story, “A Missioner Takes to Farming,” by Fr. Constantine Burns, which he submitted to The Field Afar, that I found out how much all of the manual labor tasks, including beekeeping, at Maryknoll played a large role in helping him and others to survive during wartime. Take a look!

“A Missioner Takes to Farming

The South China missioners had been living on the edge or just over the edge of danger for four years, when in December 1941, the great world struggle spread and engulfed the entire China Coast and the Southern Pacific.

[…]After the fall of Hongkong, the closing of the banks and severance of communications, most missioners took stock of their obligations and their resources, and laid plans to weather the storm. Such was the case at the Wan Fau Mission, in the vicariate of Kongmoon, where Father C. F. Burns was in charge.

[…]Father Burns called the staff in for a talk and stated the case plainly. ‘At present,’ he said, ‘we are out of touch with our Bishop and with Maryknoll. Sooner or later the Superiors will find a way to get some funds into our hands. But it is highly improbably that these funds will be adequate to carry on our present activity, due to the low exchange rate and the alarming rise in the cost of food stuffs.’

[…]Father Burns called the staff in for a talk and stated the case plainly. ‘At present,’ he said, ‘we are out of touch with our Bishop and with Maryknoll. Sooner or later the Superiors will find a way to get some funds into our hands. But it is highly improbably that these funds will be adequate to carry on our present activity, due to the low exchange rate and the alarming rise in the cost of food stuffs.’

‘Now this property is large,’ he continued. ‘Almost two acres are available for cultivation, and can possibly raise enough to ride out the storm together.’

All agreed and work was begun at once.

Father Burns had already been experimenting with native cows in an effort to develop their milking capacity. He had three cows and two calves grazing in and around the mission compound. Two more cows were secured. The surplus milk could be sold, the calves raised and the manure put back into the soil.

Then there was the old reliable papaya tree. Its fruit can be eaten ripe, made into a jam, or cooked green as a vegetable. There were fifty trees on the land already. Another fifty were planted.

Six hives of bees were brought and hung on the verandah of the house. Surplus honey could be sold, and the wax used for making altar candles.

As for the planting one must remember that this is semi-tropical country, and that with judicious arrangement three crops can be taken from the land in a year. Already the experiment has been under way for a year. What are the results?

[…]It has been a happy and a profitable experiment. And certain it is that without the ‘miniature’ farm we should not have been able to carry on as we did.”