I could say that Fr. Thomas Keefe was chosen to be the subject of this blog post because his birthday happens to fall in May, but that is merely a happy coincidence. My interest was sparked by Bishop Edward A. McGurkin’s description of him recorded in his April 1964 Shinyanga Town diary, part of the Maryknoll Fathers & Brothers Mission Diaries collection. In it, Bishop McGurkin writes, “one of the very best examples of how a missioner should encourage and help the people is given by Father Thomas Keefe at Ndoleleji. He is the classical example of the catalyst, the stimulator, the agent of liaison between his people and their needed source of technical knowledge and assistance.” I was definitely intrigued by this statement and curious to find out more about Father Keefe and the project he was planning.

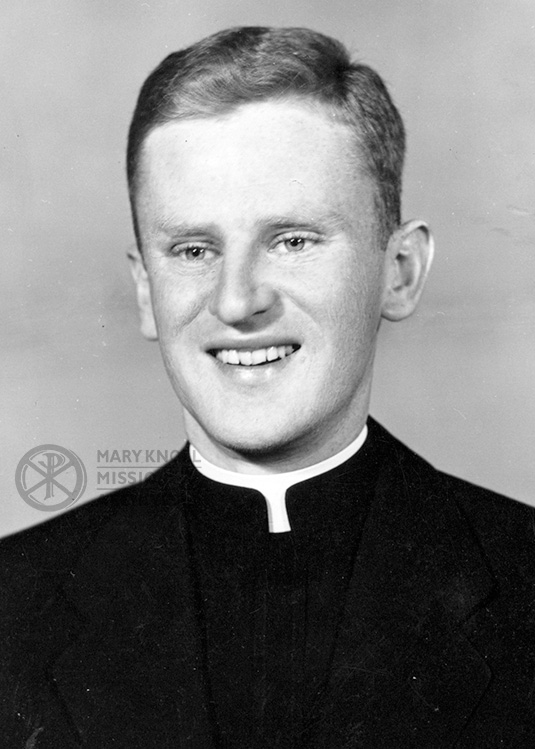

Father Thomas Keefe was born on May 28, 1928 in Poughkeepsie, New York. His elementary and high school education took place in Short Hills, New Jersey and South Orange, New Jersey respectively. After graduating from high school in 1946, Thomas entered Maryknoll Apostolic College (Venard) in Clarks Summit, Pennsylvania. His studies with Maryknoll continued at Lakewood, New Jersey and finished at Maryknoll Seminary, with a one-year Novitiate in Bedford, Massachusetts. At the completion of his studies in 1954, he received a Master of Religious Education degree. [Keefe biography, Maryknoll Mission Archives website]

His ordination to the priesthood took place on June 11, 1955 and soon after, he was assigned to Tanzania, East Africa, where he started a mission in Wira, Shinyanga Diocese, in 1958. He was then asked to start up a second mission in the Shinyanga Diocese in 1961. This location would be Ndoleleji, where a few years later after spending time with the people and seeing their needs, the aforementioned project was formulated.

Father McGurkin’s diary entry goes on to say, “[…c]onsidering the people of his parish, their hopes and their needs, and their present problems, Father Keefe sees an urgent need of trained agricultural leaders and instructors, a need of more good carpenters, and more trained mechanics, mechanics with the proper technical background and the farmer’s resourcefulness in meeting problems, mechanics who are willing to remain part of the rural community[.]

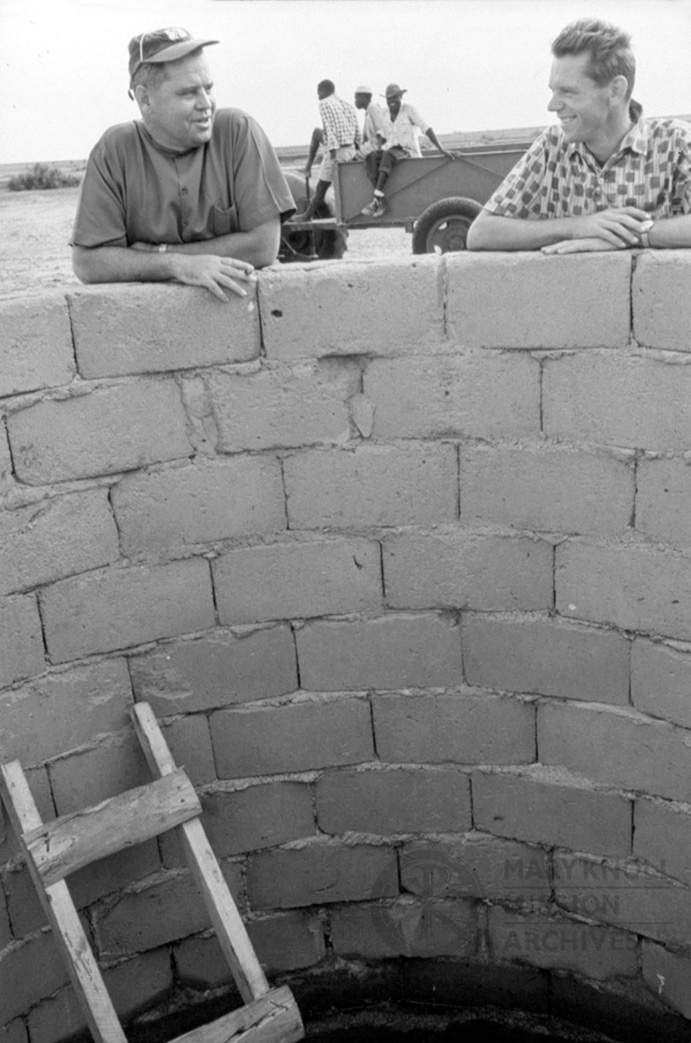

[…]While discussing this problem with his assistant Father George Cotter, he unexpectedly had an answer to his hopes and prayers one day when a young Dutch Catholic lay worker walked in and presented a plan of his own. Fran van de Laak has been giving his time and his talents to the people of Africa for the past half dozen years. He stayed at Father Keefe’s mission long enough to make a study of the country and a scientific survey of the problem.

[…]Father Keefe and Fran van de Laak have a plan. They will set up a social and technical community center at Ndoleleji. It will be a workshop, a big shed, strongly built and big enough to house Fran van de Laak and also an agricultural expert who is to come from Germany in October.

While Fran gathers a small group of apprentices around him in the workshop, learning how to use tools, how to repair their machines, learning how to estimate cost and fix prices and other bits of business administration, his companion will be with some of the men in the fields showing them how they do things in Europe.

These lessons will include methods of plowing, tie-ridging, contour plowing, the use of artificial fertilizers, tree-planting, the possibility of new fruits and new vegetables. All this, if fact, has already been started by Father Keefe on an island in the Mangu River near his mission. The people considered the land on the island to be worthless and gladly turned it over to Father Keefe for his experiments. Working it now for just over a year he has turned it into something of a magic garden: the people are astounded to see what can be done with what they considered second-rate land.

Fran van de Laak’s idea is to set up this training center, guide it through its first two years and meanwhile train one of the more promising local mechanics to take his place. He then will move on to some other part of our area and start all over again with a similar project in some other rural community that can use his help. In our big diocese of twenty thousand square miles there are many rural communities in the vast undeveloped parts of Maswa, Nassa and Shinyanga waiting for just this sort of help.

Father Keefe’s project has the support of a German Catholic relief organization [Misereor] whose motto is taken from Our Lord’s words: ‘I have compassion on the multitude…’”

After reading about the extensive plans outlined in this diary entry, I was curious to see what happened with this venture by Father Thomas Keefe and Fran van de Laak. I decided to look through our card catalog for Maryknoll Magazine to see if anyone had ever written about this project. To my happy surprise, I came across an article titled, “The Possible Dream,” in the November 1967 issue of Maryknoll Magazine, which provided information regarding the status of this particular project three years later.

“[T]he ‘Ndoleleji rural Community Centre’ became a reality in the summer of 1965.

The idea worked so well that in March of the following year Frans made this report:

‘In those early months a steady flow of tractors, lorries and cars came in for repairs. We quickly realized that we had grossly underestimated the need for repairs in the area and beyond it.’

The center attracted more repair work than it could handle so the staff had to be enlarged. Two more apprentices were added. These men were trained under the condition that they would work for at least a year in the local area afterwards.

The main purpose of the technical courses was to aid the people in their farmwork. When a tractor replaces an ox, and steel equipment, their wooden precursors, new needs arise. Father Keefe again turned to Misereor for further help. They sent a young Bavarian, the farmer Joseph Rott to assist the program.

[…H]e set about showing the advantage of proper spacing in planting, contour plowing, use of insecticides and fertilizers. New crops like soy beans, lima beans, eggplant, onions, tomatoes and okra, and new improved seed for corn were introduced.

A third element in the Ndoleleji project was the use of the windmill in irrigation. Green crops flourishing in a dark brown countryside are other signs of hope for the local people and an example to follow. Father Keefe hopes that by multiplying windmills, the people will turn this symbol of the dreamer into an instrument of progress.”

This project that was at its fledgling stage in 1964 was a success! How wonderful to not only improve the lives of the community, but also do it in a sustainable way.

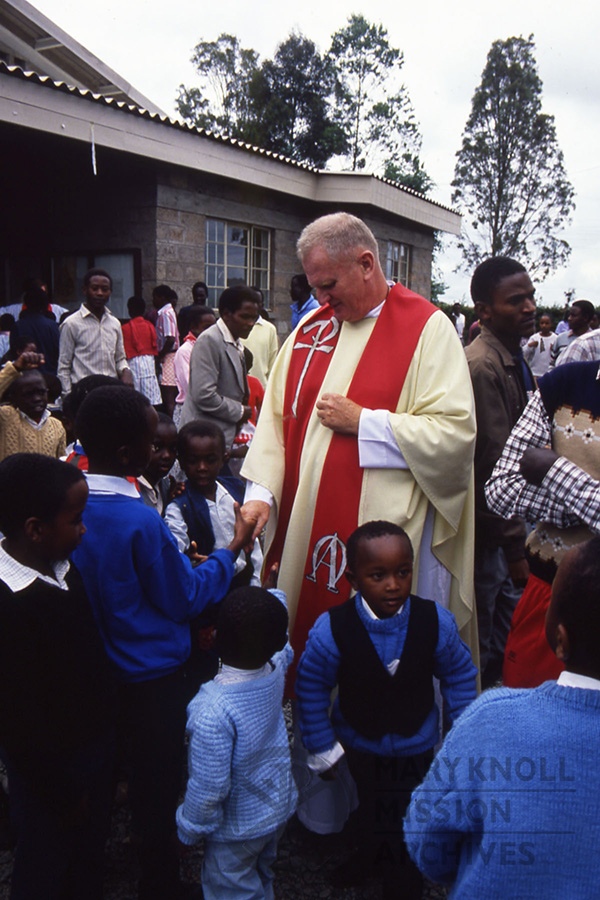

Fr. Keefe left Ndoleleji, Tanzania and returned to the United States on home leave in 1967. He would not return to mission in Tanzania. Over the next three decades, Fr. Keefe held various roles in the United States. Among them were service as a faculty member and rector of the Maryknoll Seminary, staff member of Maryknoll’s Novitiate in Hingham, Massachusetts, member of the Development Department, and director of the Office of Continuing Formation/Education. During this time, he did return to mission in Africa on two separate occasions. First in Sudan and Kenya from 1978 to 1984. In Sudan he ran a national training center for pastoral, liturgical, and catechetical education. In Kenya he worked in the parishes of Jericho and Umoja. After his time in the Development Department he returned to Kenya from 1988 to 1991, first in the Athi River Parish, then again in Umoja as pastor of the parish. Fr. Keefe joined the Retirement Community in 1999. He certainly had a vast and varied career as a Maryknoll missioner for 58 years.

In an article from 1983, Fr. Keefe reflected on “Parish life in East Africa.” You can feel the depth of his experience when you read his words. He says, “[p]arish life is the closeness you feel to families with whom you have very deep, very real, very lasting friendships so that you no longer feel like a foreigner and outsider, friendships which in the first days you never dreamed possible.” He continues his reflection, saying “[p]arish life is entering into the problems of all you meet, from the youngest to the oldest, from morning till evening, teaching them things you yourself may not believe with as much faith as you would wish – like trusting in a good God who will give us all we need, or being kind and helpful to all our neighbors, or being happy even while living with the reality of having very little.”

Fr. Keefe created lasting relationships with the people he served. He became a part of their communities and through them his faith grew. Whether it was the success of a project to benefit the community as a whole or a small connection made with one person, to Father Thomas Keefe it was all important and a part of daily parish life.