How do you pick up your life after a war? How do you begin to help people who have lost everything? Father John F. Donovan, Maryknoll missioner to China, wrote a letter in 1946 describing life in Kaying immediately after World War II.

Below is the text of his letter, which can be found in the book Maryknoll Mission Letters, Volume I, 1946.

[Please click on each photo for its caption information.]

The news of the end of hostilities came quickly and decisively, and it was most welcome. We received the news here on the eve of the Assumption. While it was still not official when we started our Masses on the feast, we – a bit prematurely – counted Our Lady’s Day as Victory Day. It was a coincidence – or was it? – that the European war ended during the month of Our Lady, and the curtain came down on the fighting over here in the Far East on her feast day. Queen of Peace!

It is hard to express just how we feel to have peace again. Since there was no actual fighting in our town, we could not feel the cessation of hostility in the same way that troops in action felt it. But we did experience a great relief. Peace means that we don’t have to have one ear always cocked for the air-raid alarm. It means that we can consider a moonlight night beautiful again – not something to be feared because unsafe. It means that the thousands of homeless can now return to their villages and land, and start from the earth and build a new life. It means that we can go ahead with our mission work with less distraction. It means that new priests and Sisters will come to help reap the harvest that awaits the Church in present-day China.

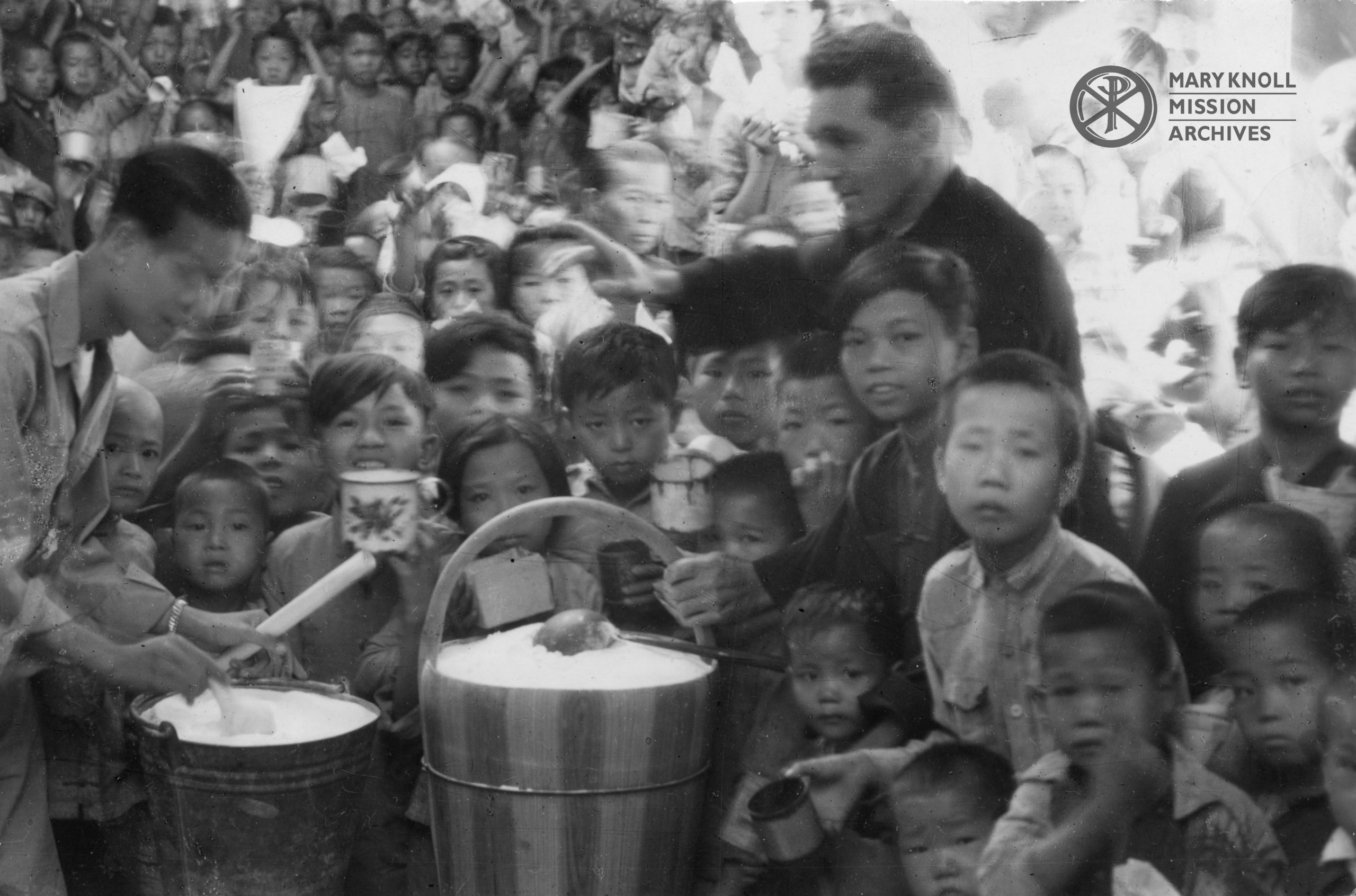

Our relief work was occupying a good portion of our time when peace came. We had about 700 people coming to the property every day for congee [a type of rice porridge]. A small industrial school where youngsters learned to make fans, baskets and other useful things with bamboo, claimed part of our time.

In August I opened a hostel to accommodate refugee women and children. The idea obviously was to provide a roof for the refugees, who otherwise would be forced to spend the nights on the roadside or in doorways. We had been trying for a long time to secure a place. Finally the near-by Buddhist monks permitted us to use part of their monastery compound, and we were able to accommodate about sixty women and children. The equipment and year’s rent were given to me by a generous American soldier, who was here when I was talking about the need. A former schoolteacher – refugee from Canton – is acting as matron.

But now we have another problem. Nine tenths of the people have asked to be helped to return to their homes. We cannot let them all go at once: that would create a problem at the other end. Bishop [Francis] Ford has arranged to set up stations along the route to Swatow. At my station here, where most of the refugees have congregated, we shall get boats and start them off – perhaps forty to a boat. They will go then to Father [Raymond] Hanrahan’s mission, in Tsungkow, eat there, and stay overnight. Next day they will continue down to Chaochu, where the French Fathers will help take care of them. Eventually many will go to Swatow, and there really start on the road to reconstruction and rehabilitation.