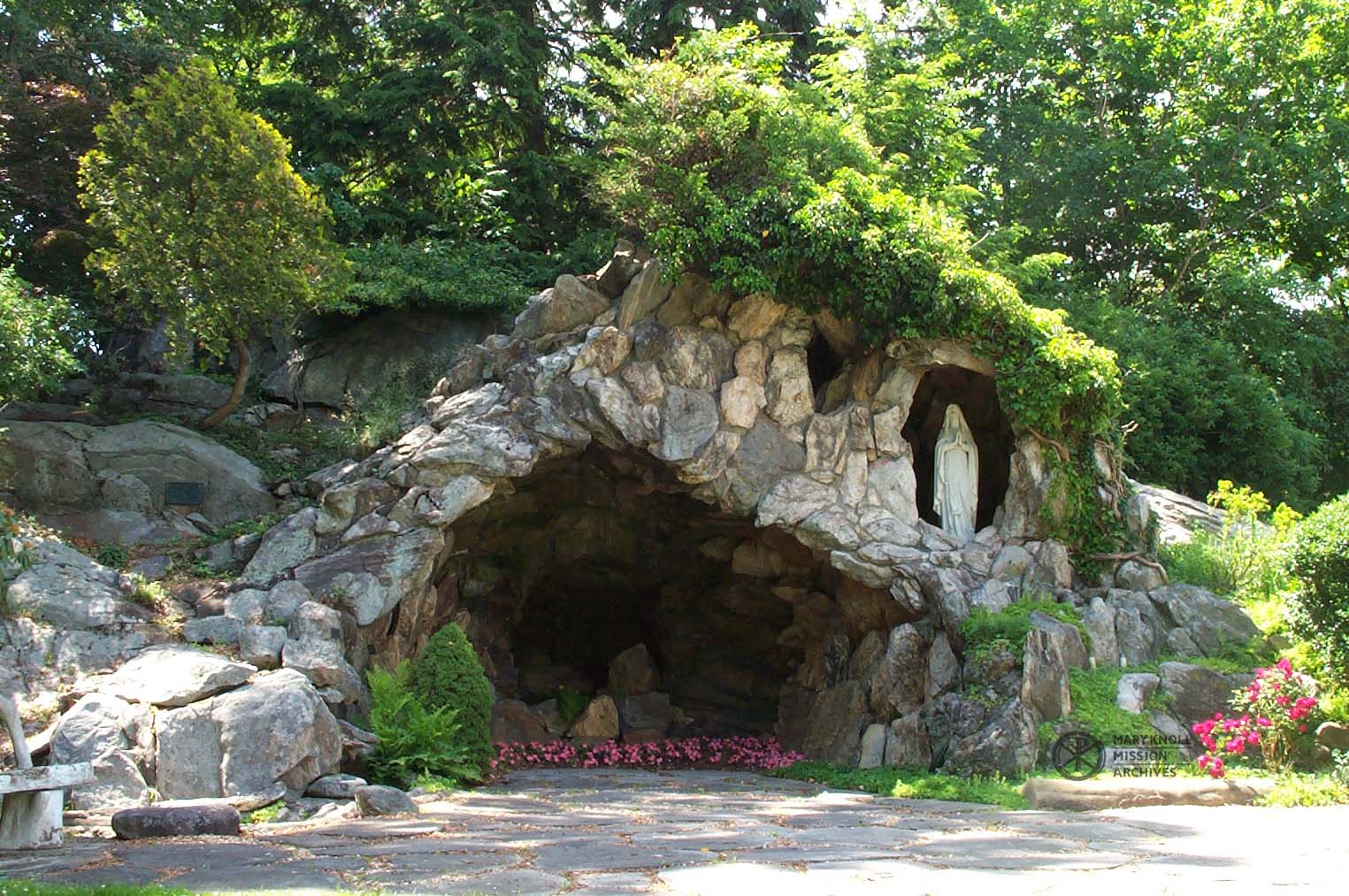

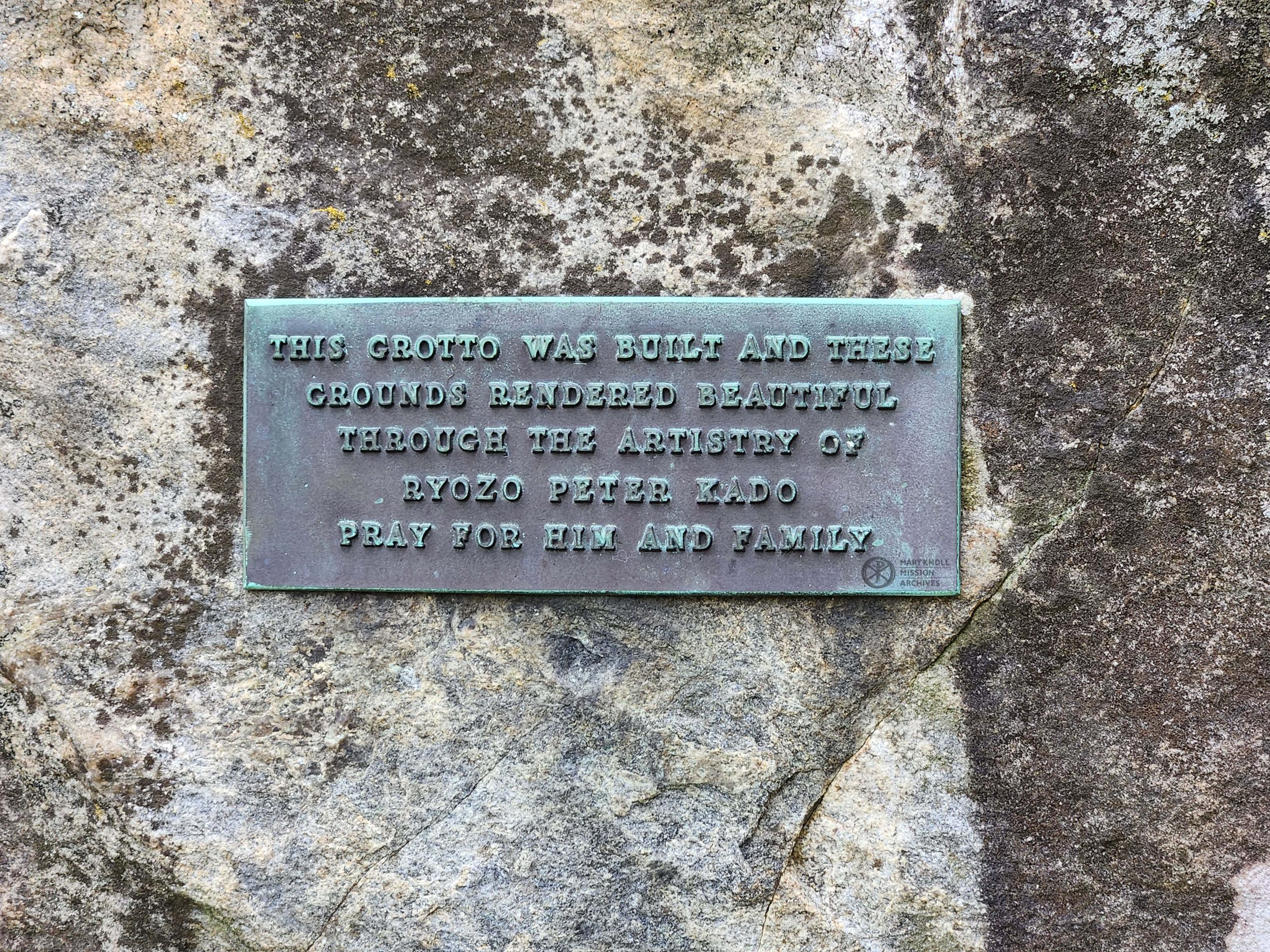

Happy May! It’s Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month in the United States. To celebrate, we’re featuring Ryozo Kado, a Japanese rock craftsman who’s well known for his Japanese-style rock gardens and Catholic shrines. A dear friend of Maryknoll, several of his works reside at the Maryknoll Sisters’ Motherhouse, including a replica of Lourdes Grotto.

Early Life

Ryozo Fuso Kado was born on February 20, 1890 in Yokokawa, Shizuoka, Japan to Eniiro and Uta (Kato) Kado. With three older sisters (Saka, Sato, and Koma) and one older brother (Naozo), he was the youngest of five siblings. His parents owned and operated a thriving tea plantation in Yokokawa, where he lived until he was seven years old. At seven, he went to live with his oldest sister Saka and her husband in Nakabe (roughly 10 miles away), though he visited his family often during school breaks and holidays.

Kado was ambitious, even as a child. When he turned 12, he begged his father’s permission to enroll in high school in Tokyo. He was determined to live in America, but was keenly aware that he could not achieve this without a solid education. His father agreed, and Ryozo went to live in Tokyo with his sister Sato, her husband, and their three little girls. He graduated high school and went on to Keio University’s Commercial School for two years.

Coming to America

With his father’s blessing, Ryozo joined the Central Tea Traders’ Association and immigrated to the United States as a tea merchant. Kado and his new colleagues spent six months in Detroit training and working as door-to-door salesmen. In 1910, he and four young men from the company moved to Cleveland and formed their own business, the Rikko Tea Company.

While business was steady, it wasn’t always lucrative. To make ends meet, Kado built several rock gardens in the Cleveland area between 1912 and 1915. His youthful appreciation for beautiful landscaping turned into creating beauty for others, though he was often dissatisfied with his final results. Japanese stonework evolved into his passion and, in 1915, he left the Rikko Tea Company to find a master craftsman to apprentice under in Los Angeles.

Finding Nishimura

Kado required a Japanese teacher, so returning to the West Coast was his best option. While San Francisco was known for its large Japanese population, Kado chose Los Angeles because of its growing Japanese business sector. By 1915, Japanese immigrants had established their own “Little Tokyo” within Los Angeles and a Japanese consulate was opened to accommodate the growing population (U.S.D.I., 2002).

It was a stroke of luck that Kado found Chotaro Nishimura living in Los Angeles. Renowned designer of the Royal Gardens in Tokyo and the President’s Palace in Mexico City, Nishimura was a fourth generation rock craftsman whose family had beautified Japan for over 100 years.

Kado was politely declined when he first requested a job with the master craftsman. Determined to make his dream a reality, Kado walked daily to Nishimura’s nursery on Santa Monica Boulevard until Nishimura finally agreed to hire him. Kado worked as a laborer for three years before Nishimura began sharing his techniques.

In 1919, Kado decided to leave Nishimura’s nursery and open his own landscaping business with a friend. The two enterprising partners established themselves on an acre-lot in Hollywood, and began the hard work of growing their business. During this time, Kado also began his suit to marry Hama Nishimura, one of Chotaro Nishimura’s daughters. With Mr. Nishimura’s permission, Ryozo and Hama were married on January 21, 1922. Their marriage solidified Kado as a fifth generation member of the Nishimura rock craftsmen.

Becoming Catholic

The next seven years tested Ryozo and Hama’s marriage as they endured together “for better and for worse”. Harsh frosts destroyed their plant nursery several times. Supported by each other, they restarted their family business again and again. Their household grew as they welcomed two children, Louis and Ida, into the world. By 1929, “Wilshire Cactus and Rock Craft Company” was a thriving business.

That same year, Kado had a chance meeting with Mrs. August Luer, a devout Catholic. The Luer family had commissioned a shrine to Our Lady of Grace for their garden. Mrs. Luer was dissatisfied with the first craftsman’s work. Mr. Kado’s work was beautiful; could he build a new shrine for her? And a shrine to St. Anthony for her daughter, Mrs. Charles Von der Ahe?

His time with the Luer and the Von der Ahe families solidified a new career path, and redirected him spiritually towards Catholism. He was baptized in 1929 by Fr. Hugh Lavery at the Maryknoll Mission in Los Angeles. Fr. Lavery chose Peter for his confirmation name. This name was clearly selected for him with thought and care, as “Peter” translates from Greek to “rock” or “stone”. Kado admits in an unpublished manuscript that he was not fond of the name, but “the idea of the rock man is good”. While Ryozo continued to create magnificent rock gardens, garden exhibitions, and public gardens throughout his career, he became famous in Catholic circles for his shrines. His labors of love can be seen here at Maryknoll, NY and throughout Los Angeles County. It’s estimated that Kado built 75-80 religious shrines during his lifetime.

Manzanar Relocation Center

The Kado family’s fortunes changed yet again when the United States entered World War II on December 8, 1941, the day after Japan’s military attack on Pearl Harbor (Wiki, 2024). Rising racial prejudice and fears of espionage by Japanese Americans led to President Franklin D. Roosevelt signing Executive Order 9066 in February 1942. The Executive Order allowed Military Areas to be established, and for the forcible removal of people with Japanese ancestry from these areas (U.S.D.I., 2021).

Louis (16) and Ida (14) were still teenagers when they were interned. Louis was forced to return the brand-new car he had worked so hard to purchase; Ida’s international doll collection was broken up and destroyed. Ryozo and Hama were forced to either sell, destroy, or leave their belongings with non-Japanese friends and neighbors. Like so many other internees, their house was wrongfully sold by the “friend” who promised to care for it until they returned.

On April 7, 1942, the Kado family entered the Manzanar War Relocation Center. They were among the 11,070 Japanese Americans processed through Manzanar until its closing on November 21, 1945 (U.S.D.I., 2021).

Maryknoll at Manzanar

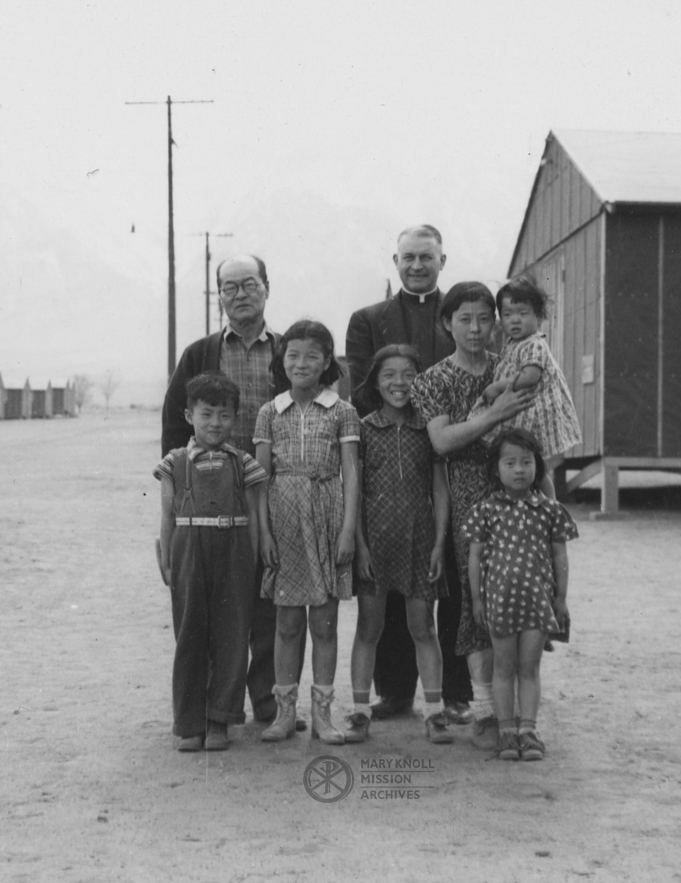

The familiar faces of friends and neighbors included Maryknoll Sisters and Maryknoll Fathers from the Maryknoll Mission in Los Angeles. Sr. Susanna Hayashi and Sr. Bernadette Yoshimochi could have escaped internment by returning to the Motherhouse. Instead, they volunteered to live in solidarity with their community. They took over one of the barracks and made a multipurpose space including their living quarters, classroom, consultation room, parish hall, and a church on Sundays.

Fr. Hugh Lavery was not allowed to live inside Manzanar. That did not deter him from serving people in need. He traveled six miles from the town of Lone Pine to perform Mass every day. Fr. Lavery was later joined by Fr. Leo J. Steinbach, following his release from internment in Japan.

Maryknoll Fathers and Maryknoll Sisters inspired many individuals at Manzanar to join the Society or the Congregation. These include:

“I went out of the stuffy hut and looked around. The valley was hemmed in on three sides by mountains. Mount Whitney soared in the west, majestic and unattainable. Close at hand was nothing of beauty. Monotonous rows of barracks, 100 ft. long, 30 ft. wide, baked in dry heat under their tar paper roofs. The rough lumber of their walls met the earth with a thud. There were no house-hugging plants to soften the blow. This was a land of cactus, centipedes, rattlers and scorpions. I was in charge of the gardens. Gardens?”

Gardens in the Desert

On his first day at Manzanar, an Army officer assigned Kado to care for the property’s non-existent gardens. Thanks to an endless supply of water rolling off Mount Whitney, Ryozo was able to rise above and fulfil the assignment. He took his charge seriously and, along with his son Louis, rounded up as many able-bodied men and teenagers as he could to assist him. Together they built a pumping station, rock gardens, and ponds; they planted and grew gardens, trees, and miniature farms throughout the blocks of Manzanar.

Unfortunately, most of these gardens were lost to time and dust storms following the center’s closure. An important memorial tower has survived erasure, however. Manzanar Ireito, or Consoling Spirits Tower, was built in 1943 as a testament to the internees who were only granted freedom from Manzanar in death. A collaboration between Buddhist minister Shinjo Nagatomi and devout Catholic Ryozo Kado, this monument would not have been possible without the financial contributions of the entire community. Both Catholics and Buddhists continue to make pilgrimages to Manzanar Ireito each year to pray for the souls of Manzanar’s dead.

To Maryknoll and Back Again

The Kados lived in Manzanar for 15 months. Through the intersessions of Sr. Susanna, Sr. Bernadette, and Mother Mary Joseph, they were able to secure the appropriate working papers for Ryozo to leave Manzanar and landscape for the Motherhouse. The Kado family was relocated to a small cottage on the Sisters’ grounds where they lived for three years.

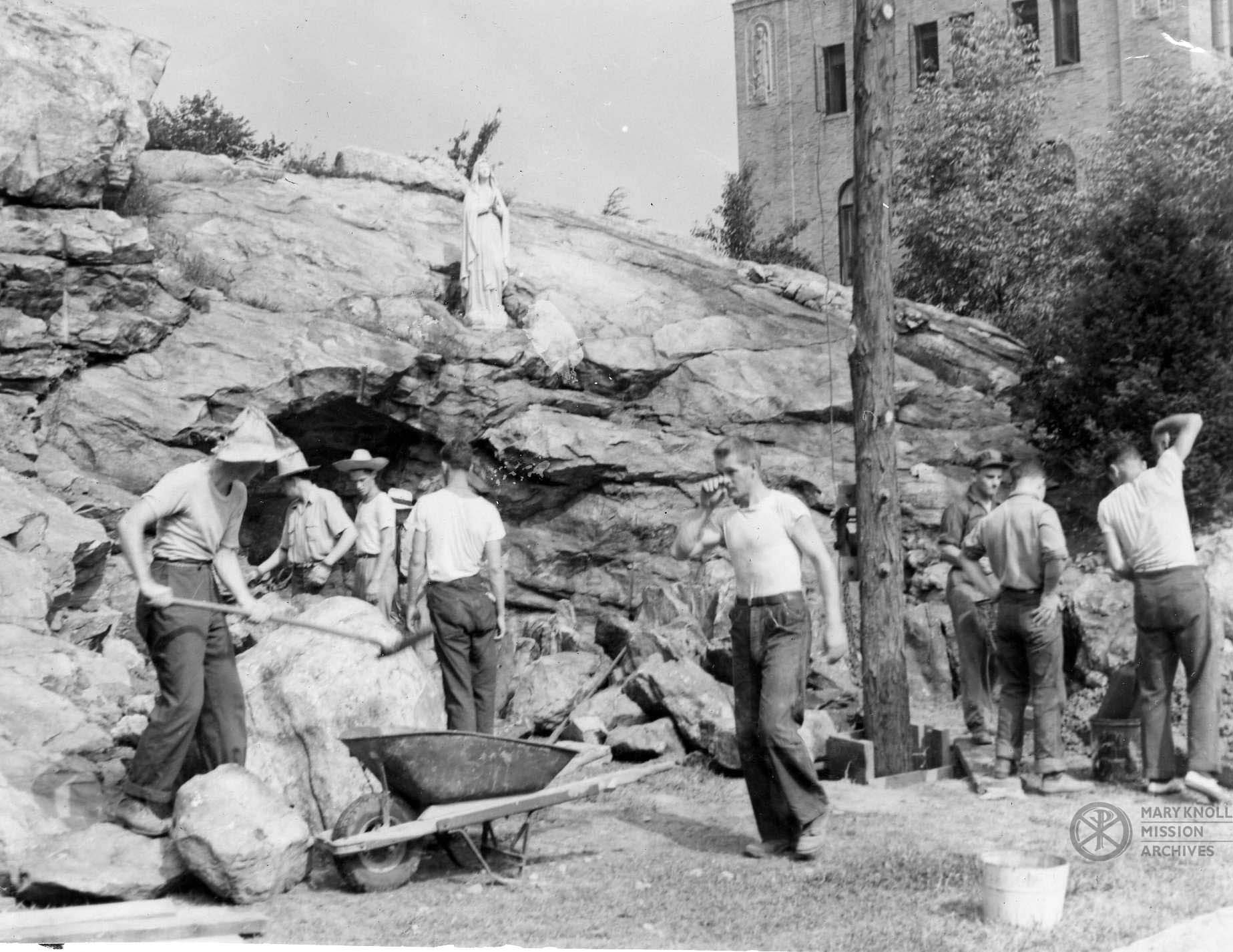

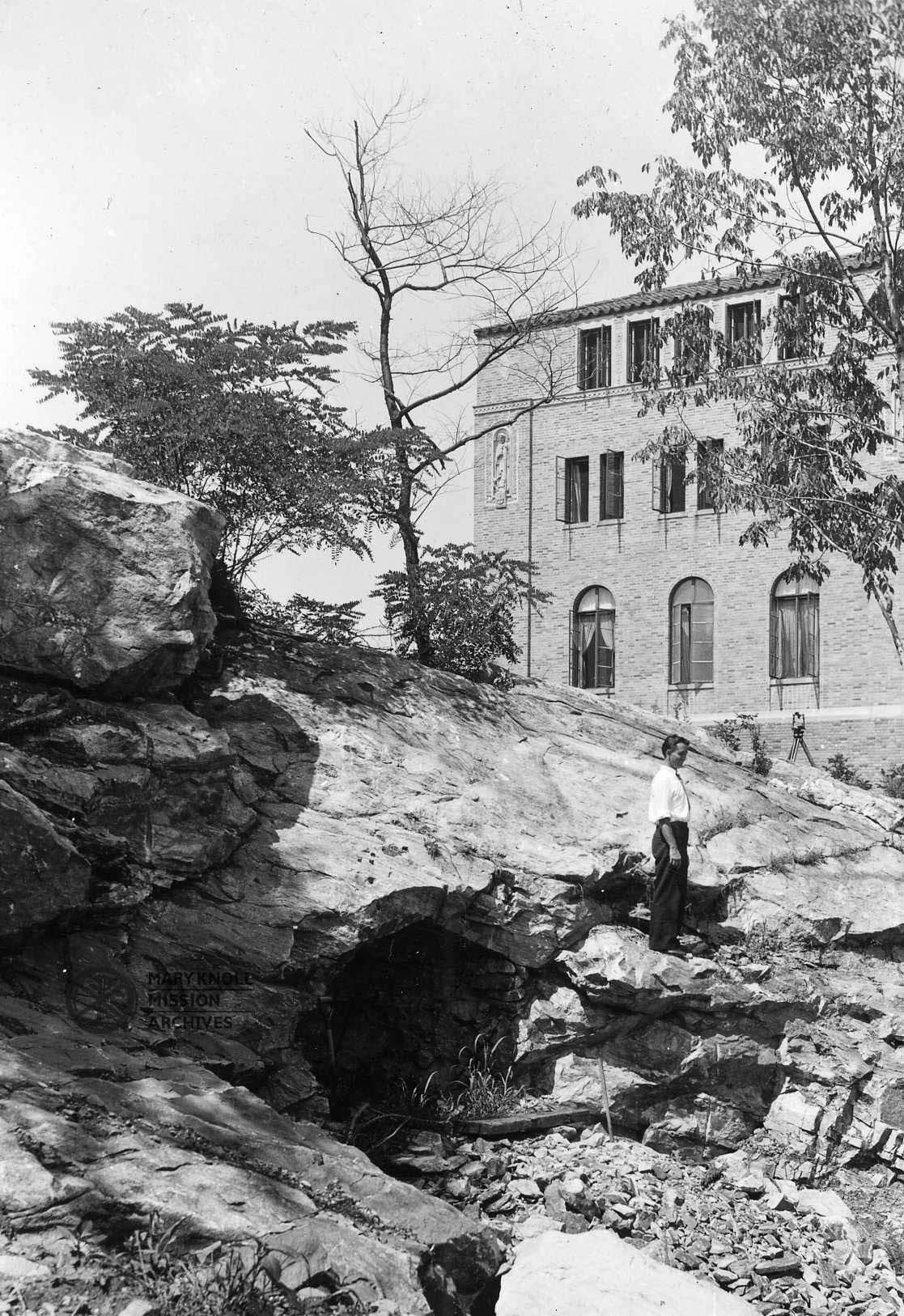

Mother Mary Joseph and Hama became friends during their time here. Louis and Ida were enrolled in the seminary and the novitiate to continue their education. Ryozo gave his undivided attention to beautifying the Motherhouse grounds. Of special note is the stunning Our Lady of Lourdes Grotto he built for the Sisters.

In 1946, the family returned to Los Angeles amid tearful goodbyes. Ryozo and Hama rebuilt their lives and family business once again. Mr. Kado was hired by the Archdiocese of Los Angeles as their Superintendent of Landscape Architecture. The couple remained forever grateful to the Maryknoll Sisters and continued corresponding with Mother Mary Joseph until her passing in 1955.

Dreams Come True at Last

Despite living in the U.S. since 1910, Kado was unable to become a citizen until Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1952. Racial restrictions on immigration and racially targeted laws, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Asian Exclusion Act of 1924, kept people of Asian descent from immigrating and becoming citizens for decades. Repealing these laws created new opportunities for thousands of people, including the Kado family.

Ryozo Kado became an American citizen on February 12, 1954, alongside his beloved wife Hama. They celebrated by making a pilgrimage to the original Lourdes Grotto in France.

Later in 1954, the California Board of Landscape Architects awarded him an honorary degree of landscape architecture. Kado’s star continued to rise. He became known as the “Wizard with Rocks” following Frank J. Taylor’s article in the Saturday Evening Post, published on August 5, 1961. Despite his growing fame and demand as a landscape architect, Kado returned to Maryknoll every summer to visit and perfect his gardens here. He continued to construct gardens and shrines until his retirement from the Los Angeles Archdiocese on August 1, 1977. Kado was 87 years old.

Ryozo Kado died in Los Angeles on March 8, 1982. Ryozo and Hama are buried together forever in Holy Cross Cemetery, Culver City, near the Lourdes Grotto he built there.

Religious Shrines

Kado built roughly 75-80 religious shrines during his lifetime. The numbers change depending on the source (75 according to a news article by John Truxaw; 80 according to St. John’s Seminary website). Unfortunately, we may never know the true extent of his work. Many of his shrines were built on private property and remain unlisted as landmarks. The following is a list of shrines I have been able to locate.

Shrine to Our Lady of Grace, August Luer estate, Los Angeles, CA (1929) (#1)

Natural rock shrine to St. Anthony, Charles Von der Ahe gardens, Los Angeles, CA (1929) (#2)

Trellis Shrine for St. Therese, Carmel of St. Teresa cloister gardens, Alhambra, CA (1929) (#3)

Our Lady of Lourdes Grotto, August Luer estate, Los Angeles, CA (1929) (#4)

Lourdes Grotto, Carmel of St. Teresa cloister gardens, Alhambra, CA (1930) (#5)

Stations of the Cross, Carmel of St. Teresa, Alhambra, CA (c. 1930-1931)

Lourdes Grotto, St. Vibiana’s Cathedral, Los Angeles, CA (c. 1930-1935)

Our Lady of Fatima, St. Andrew’s, Pasadena, CA (c. 1930-1935)

Lourdes Grotto, St. Francis Xavier School, Los Angeles, CA (c. 1930-1935)

Lourdes Grotto, Church of the Immaculate Conception Gardens, Los Angeles, CA (1936)

“Lourdes of the West” shrine, St. Elizabeth Church, Altadena, CA (1936-1939)

Marian Lourdes Grotto, St. John’s Seminary, Camarillo, CA (c. 1930s)

Lourdes Grotto, Marymount College (Marymount California University), Rancho Palos Verdes, CA (c.1930s)

Shrine, Loyola High School, Los Angeles, CA (c. 1930s)

Shrine, Holy Name parish, Los Angeles, CA (c. 1930s)

Shrine, Maryknoll Sisters Convent, Los Angeles, CA (c. 1930s)

Stations of the Cross, St. John’s Major Seminary, Carmarillo, CA (c. 1940-1941)

Miraculous Medal, Ferndale Ranch (Doheny estate), Santa Paula, CA (1940-1941)

Lourdes Grotto, Home of Fibber McGee & Molly, Los Angeles, CA (1941-1942)

We know Kado was working in Long Beach and Pasadena just prior to his internment at Manzanar. There are likely shrines in these areas that I have been unable to locate.

Manzanar Memorial Shrine, Manzanar National Historic Site, CA (1943)

(Also known as Manzanar Ireito and Consoling Spirits Tower)

Lourdes Grotto, Maryknoll Sisters, Maryknoll, NY (1944)

Good Shepard Shrine, Maryknoll Sisters, Maryknoll, NY (1946)

Rock wall holding 3 shrines, Holy Cross Cemetery, Culver City, CA (c. 1946-1954)

Lourdes Grotto, Holy Cross Cemetery, Culver City, CA (c. 1946-1954)

(Ryozo and Hama Kado are buried here, directly across from the Lourdes Grotto.)

Our Lady of Lourdes, Kado family property, Los Angeles, CA (1957)

Lourdes Grotto, Maryknoll Hospital, Monrovia, CA (c. 1961-1963)

Dates Unknown

Pieta Shrine, Holy Cross Cemetery, Culver City, CA

Grotto, St. Francis Xavier Church – Japanese Catholic Center, Los Angeles, CA

Tekawitha Shrine, Maryknoll Sisters, Maryknoll, NY

Statue of Saint Kateri Tekakwitha, Maryknoll Sisters’ Motherhouse, Maryknoll, NY. The pedestal was constructed by Ryozo Kado.

Construction of Our Lady of Lourdes Grotto at the Motherhouse, 1944

Construction of Our Lady of Lourdes Grotto at the Maryknoll Motherhouse, Maryknoll, NY. 1944

Rock garden built by Ryozo Kado inside the Rogers College Library, Maryknoll, NY

Interested in learning more about Maryknoll? You can contact the Archives at:

Maryknoll Mission Archives

PO Box 305, Maryknoll, New York 10545

Phone: 914-941-7636

Office hours: 8:30 am-4:00 pm Monday-Friday

Email: archives@maryknoll.org

Website: www.maryknollmissionarchives.org

References:

Beckwith, R. J. (2008, January 25). Landscape Gardens and gardeners at Manzanar Relocation Center. Discover Nikkei. https://discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2008/1/25/landscape-manzanar/

Bishop James A. Walsh. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2019, July 25). Retrieved from https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/bishop-james-a-walsh/

Brightwell, E. (2019, June 7). Southland Parks – A Directory of Asian gardens in Los Angeles. Eric Brightwell. https://ericbrightwell.com/2016/05/20/asian-gardens-of-los-angeles/

Cairns, M. (2023, August 23). Our lady of Lourdes Grotto. Maryknoll Mission Archives. https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/our-lady-of-lourdes-grotto/

California Audiovisual Preservation Project (CAVPP). (2001). Louis Kado interview. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/cainmnh_000026

“California Marriages, 1850-1945”, database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:H9ZH-SPPZ : 24 March 2020), Ryozo F. Kado, 1922.

Father Bryce T. Nishimura, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2024, February). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-fathers-bro/father-bryce-t-nishimura-mm/

Father Hugh T. Lavery, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2014, April 22). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-fathers-bro/father-hugh-t-lavery-mm/

Father Leo J. Steinbach, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2014, April 17). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-fathers-bro/father-leo-j-steinbach-mm/

Father Thomas W. Takahashi, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2014, April 16). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-fathers-bro/father-thomas-w-takahashi-mm/

Frank J. Taylor: At the Saturday evening post. The Saturday Evening Post. (2018, April 9). https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/author/fj-taylor/

Immigration Act of 1952. Densho Encyclopedia. (2020, July 7). https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Immigration_Act_of_1952/

Kado, R. F., & del Rey, Sr. M. (1964). Unpublished manuscript of Ryozo F. Kado. Maryknoll Mission Archives.

Langedyke, M. L. (2011, April 21). “Lourdes of the West”: the history of the St. Elizabeth grotto. Altadena blog. https://altadenablog.altadenahistoricalsociety.org/archive/www.altadenablog.com/2011/04/lourdes-of-the-west-the-history-of-the-st-elizabeth-grotto.html

LaRocque, G. L. (2010, October 11). Ryozo Fuso “Louis” Kado (1890-1982). Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/59965368/ryozo-fuso-kado

Ling, S. (2022, August 5). Maryknoll sanatorium in Monrovia, California. Discover Nikkei. https://discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2022/8/5/maryknoll-sanatorium/

Los Angeles Public Library. (n.d.). Lourdes of the West. Calisphere. https://calisphere.org/item/c16982f7905d8288cb20debdb77d4e1b/

Mother Mary Joseph Rogers. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2019, July 25). Retrieved from https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/mother-mary-joseph-rogers/

Plunkett. (n.d.). Lourdes Grotto, church of the immaculate conception gardens, Los Angeles. Calisphere. https://calisphere.org/item/c719197daaca7ad487196c767c44f841/

Properties and grounds collection, 1912-2019. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2019). https://maryknollmissionarchives.libraryhost.com/index.php?p=collections%2Fcontrolcard&id=78&q=grotto

St. Francis Xavier School. (2024). https://sfxschool.org/

The setting of St. John’s seminary. St. John’s Seminary. (2023). https://stjohnsem.edu/the-campus

Sister Ann Teresa Kamachi, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2023, July). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-sisters/sister-ann-teresa-kamachi-mm/

Sister Anna Otome Hayashi, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2014, April 29). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-sisters/sister-anna-otome-hayashi-mm/

Sister Bernadette Yoshimochi, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2014, April 24). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-sisters/sister-bernadette-yoshimochi-mm/

Sister Thecla (Mutsuye) Tsuruda, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2023, April). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-sisters/sister-thecla-mutsuye-tsuruda-mm/

Sister Yae Ono, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2014b, April 24). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-sisters/sister-yae-ono-mm/

Tavoda, M. P. (2015, May 11). Honorable Mention Research Paper: A “Land You Could Not Escape yet Almost Didn’t Want to Leave:” Japanese American Identity in Manzanar Internment Camp Gardens. Chapman University Digital Commons. https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1020&context=undergraduateresearchprize

U.S. Department of the Interior. (2002, January 1). Manzanar NHS: Historic Resource Study/Special History Study (Chapter 9). National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/manz/hrs9b.htm#:~:text=Of%20the%207%2C444%20Japanese%20in,take%20care%20of%20Japanese%20depositors.

U.S. Department of the Interior. (2021, October 22). Japanese Americans at manzanar. National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/manz/learn/historyculture/japanese-americans-at-manzanar.htm

U.S. Department of the Interior. (n.d.). History of the manzanar cemetery. National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/places/history-of-the-manzanar-cemetery.htm

U.S. Department of the Interior. (n.d.). Manzanar National Historic Site. National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/manz/index.htm

“United States, War Relocation Authority centers, final accountability rosters, 1942-1946,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6843-V49Y : 15 December 2021), Fuso, 1 Jun 1942; citing roster, family no. , line , NARA microfilm publication M1865 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2001).

Wikimedia Foundation. (2023, April 26). Lourdes Grotto. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lourdes_grotto

Wikimedia Foundation. (2023, June 2). Our lady of Lourdes. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Our_Lady_of_Lourdes

Wikimedia Foundation. (2024, April 3). Immigration and nationality act of 1952. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immigration_and_Nationality_Act_of_1952

Wikimedia Foundation. (2024, February 26). Fibber McGee and Molly. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fibber_McGee_and_Molly

Wikimedia Foundation. (2024, April 23). Attack on Pearl Harbor. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attack_on_Pearl_Harbor