Maryknoll Memoirs – A Work in Progress

If you’ve ever looked through the Biographies section on our website, you may have noticed that not all bios are equal. Some paint detailed portraits of the person’s life and mission work while others are more like a thumbnail sketch, leaving ample room for questions about the gaps. (See Father Thomas A. Barry, MM for a particularly short example.)

We don’t update or change these biographies because they are record transcriptions created by Maryknollers following an individual’s death. They have historic significance, even if they don’t tell the full story. When the Archives received a request about Fr. Thomas Barry’s life, the hard work and research used to recreate his life evolved into a blog post. It was written to celebrate his life and make his story more accessible to the public. This project evolved into the Maryknoll Memoirs series.

Maryknoll Memoirs:

- Fr. Thomas A. Barry: Life and Legacy in Japan

- Maryknoll Memoirs: Fr. John J. Massoth

- Maryknoll Memoirs: Sr. Marianna Akashi

This series celebrates the lives of Maryknoll missioners whose biographies simply do not do them justice. Today, we celebrate the life of Bro. Gonzaga Chilutti. Despite the hardships of his youth, he survived and endured without losing his compassion for others. His expertise as a mechanic kept Maryknoll’s Pando Vicariate mission running in the depths of Bolivia’s jungles and waterways, allowing Maryknoll to serve rural populations in need.

Dear Reader,

Before you dive into Bro. Gonzaga’s tale, we would like to warn you that this memoir may be difficult for some readers due to its content. Bro. Gonzaga lived through several challenging periods of world history, during which several million people died. His story reflects the hardships that so many of our ancestors endured. This story is important to tell, however, it does not have a happy ending.

If you are looking for more uplifting stories, we would like to offer the following recommendations instead:

Maryknoll’s Military Chaplains

Fr. Thomas Keefe – The Possible Dream

Wishing you all the best,

Maryknoll Mission Archives

Charles M. Chilutti – The Early Years

Charles Michael Chilutti was born on November 9, 1912 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was the youngest son of Italian immigrants, Luigi Chilutti and Angela Conri. (Anglicized versions of their names appear in U.S. records as Louis Chilutti and Angelina Cane.) Records suggest the Chiluttis and their oldest children, Joseph and Jennie, immigrated to the United States and settled in Philadelphia sometime between 1904 and 1907. The family continued to grow with the addition of Maria (b.1908), Ernest (b.1910), and Charles (b.1912). While Charles was still an infant, the Chiluttis returned to Italy for three years.

Records suggest the Chiluttis arrived in Europe prior to the start of World War I. It’s difficult to imagine what they would have experienced as the war continued to escalate, threatening themselves, their extended family, and neighbors. We know they managed to book passage back to the U.S. and return to Philadelphia, however, the family’s struggles did not end here. In 1918, Luigi Chilutti fell ill and died from the Influenza epidemic as it spread rapidly throughout Philadelphia.

The death of the Chiluttis’ patriarch shattered the family. Angela was unable to support five children on her own; she did not speak fluent English and her health was fragile. With limited options, she was forced to make an agonizing choice. Joseph, Jennie, and Maria were sent to live with extended family across the city. Ernie and Charlie, too young to work, were sent to St. John’s Orphan Asylum.

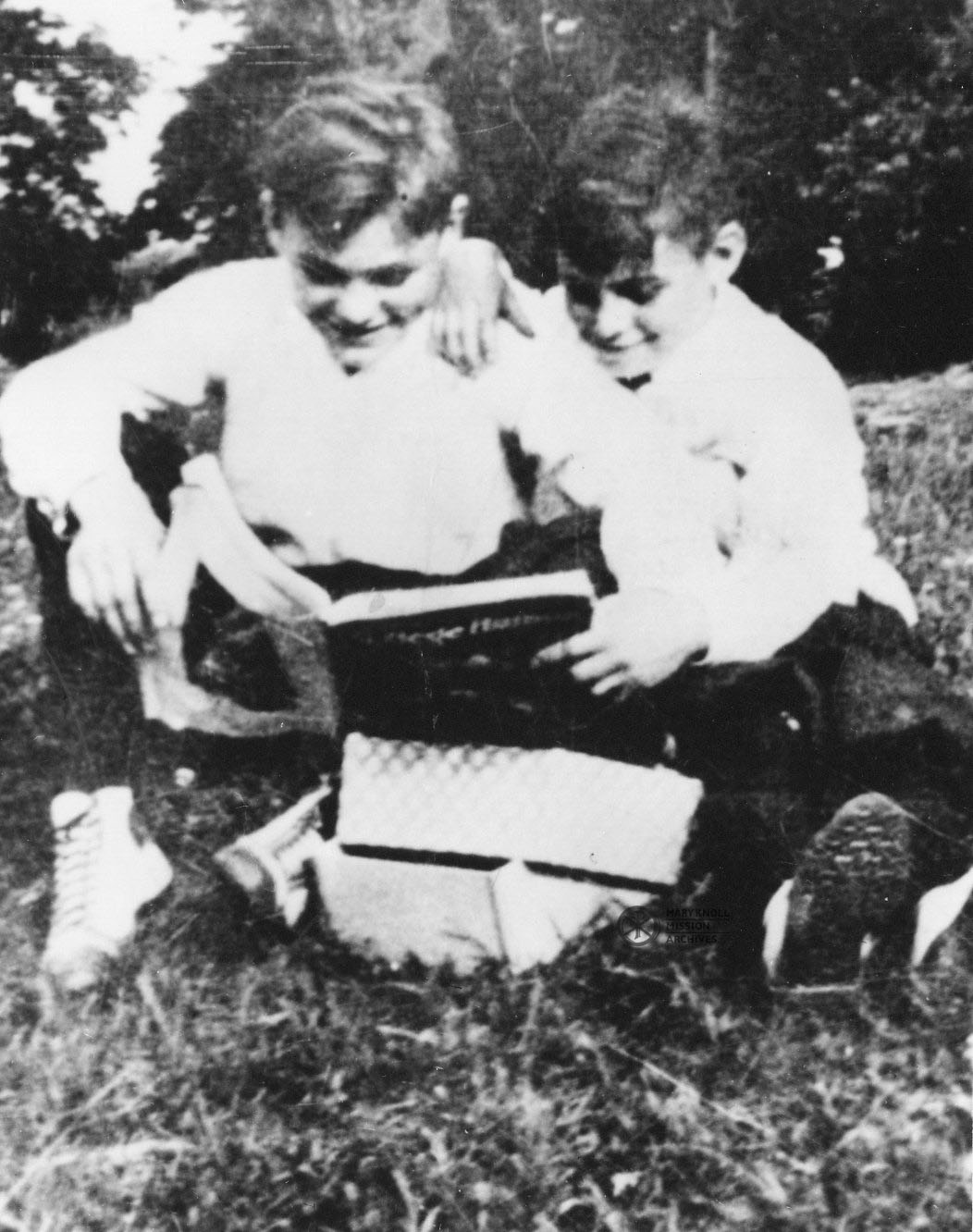

Evidence suggests this unmarked photo is a rare image of Ernie and Charlie as children, taken during their time at St. John’s Orphan Asylum.

Many of the boys at St. John’s shared similar situations to the Chilutti boys; their families were destitute through no fault of their own. Poverty, illness, and widowhood were the most likely reasons why their living parents or relatives were unable to care for them. The Sisters of St. Joseph kept these vulnerable boys safe, and ensured they received appropriate care and a Catholic education.

A testament to her undying love, Angela Chilutti worked hard to stay present in her beloved children’s lives. According to Bro. Gonzaga’s biography, Something for God, their mother visited St. John’s quite frequently. Despite their physical separation, Charlie “had always felt that he and his mother were close” (Lyons). Ernie and Charlie remained devoted brothers and best friends during their time here, eventually aging out of the orphanage.

St. John’s Orphan Asylum

One of the oldest orphanages in Philadelphia, St. John’s Orphan Asylum for Boys was originally established in 1797 by the Catholic Women’s League and laity from the St. Vincent de Paul Society to combat yellow fever. The yellow fever epidemic of 1793 devastated the city, and Philadelphia’s most vulnerable populations suffered as the disease continued to spread every year. St. John’s nursed sick boys while its counterpart, St. Joseph’s Asylum, cared for the city’s girls.

By 1847, the Sisters of St. Joseph had taken over running the orphanage. As Philadelphia’s population of orphaned and destitute children grew, the Sisters housed and cared for more children, eventually relocating from Seventh and Spruce Streets to a larger facility at 49th A. Wyalusing Avenue. St. John’s had changed dramatically by the time the Chulitti boys stepped through its doors in 1918. The links below offer photos of the orphanage as Ernie and Charlie may have seen it.

St. John’s Orphan Asylum – Historic Photographs

Postcard of St. John’s Orphan Asylum, c. 1910

Image courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia https://digital.librarycompany.org/islandora/object/digitool%3A97271

St. Francis and the Job Market

Following their time at the orphanage, both brothers were able to continue their education at St. Francis’ Vocational School. Career training was not available to everyone in the care of Philadelphia’s Catholic Social Services; Ernie and Charlie would have been selected for this life-changing opportunity. Their ability to enter the job market as skilled laborers, instead of teenagers with no work experience, made a significant difference towards becoming self-sufficient adults. At St. Francis, Charlie trained to be a mechanic and learned critical skills that served him for the rest of his life. He graduated in 1928.

It’s unclear whether Ernie and Charlie lived at St. Francis during their final years of study. We do know that the Chilutti boys were able to find employment post-graduation. Charlie was hired as an apprentice machinist building soda fountains. When the economy took a turn for the worse in 1929, Charlie was laid off but found less glamourous work mixing and bottling soft drinks. He was eventually laid off from this job too.

By the 1930 United States Census, both Chilutti boys were unemployed and living with their older sister Jennie, now Mrs. Charles Messa.

The Great Depression

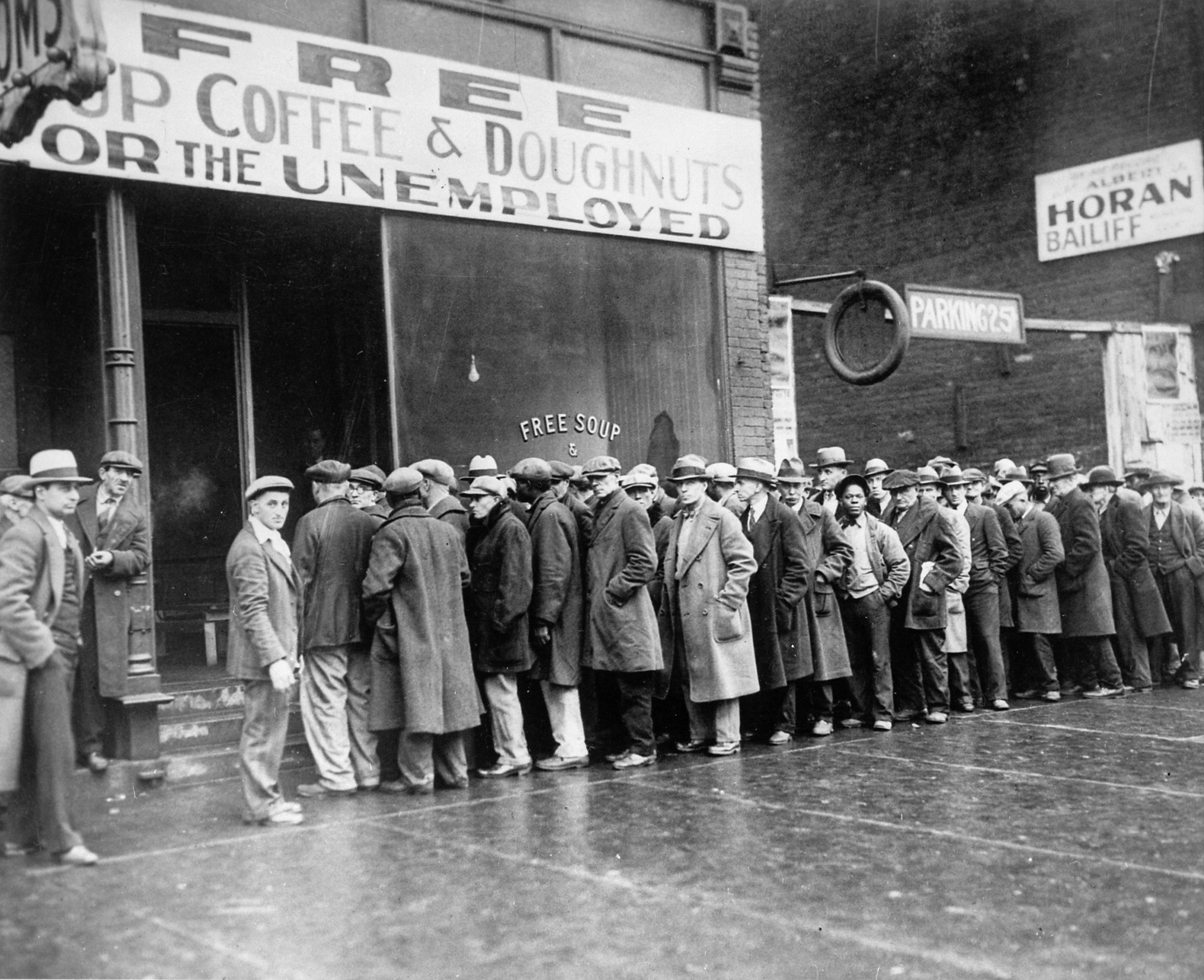

The Wall Street stock market crash of October 1929 impacted an untold number of Americans. Its shock waves were felt around the world, damaging global economies until 1939. The Chilutti siblings did not escape its ravages. While Jennie’s husband, Charles, was thankfully still employed by 1930, his was the only income supporting a household with four adults and three children. Money would have been extremely tight. Conscious of the financial danger to Jennie’s family, Ernie and Charlie decided to leave Philadelphia in hopes of finding work elsewhere.

The brothers spent the next couple of years homeless and traveling along the East Coast, South, and West Coast trying to find work and survive. Their experiences during this phase of their life were familiar to an increasing number of Americans as the economic downturn deepened into a depression. Hitch-hiking, trading labor for food and services, and generally relying on the kindness of strangers were normal parts of their daily lives. Hunger was a constant companion. Like many men and women, they increasingly turned to hopping freight trains to survive despite it being illegal.

Charlie was arrested several times during his travels for train hopping, vagrancy, and “appearing suspicious”. He was never jailed or put on trial thanks to the compassion of certain officers and Charlie’s growing network of friends across the country (some of whom knew lawyers). In 1931, Ernie found work in Los Angeles, CA through an acquaintance. Charlie continued on without him, eventually finding work as an orderly for the San Francisco City and County Hospital.

Unemployed men queued outside a depression soup kitchen opened in Chicago by Al Capone, February 1931. Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

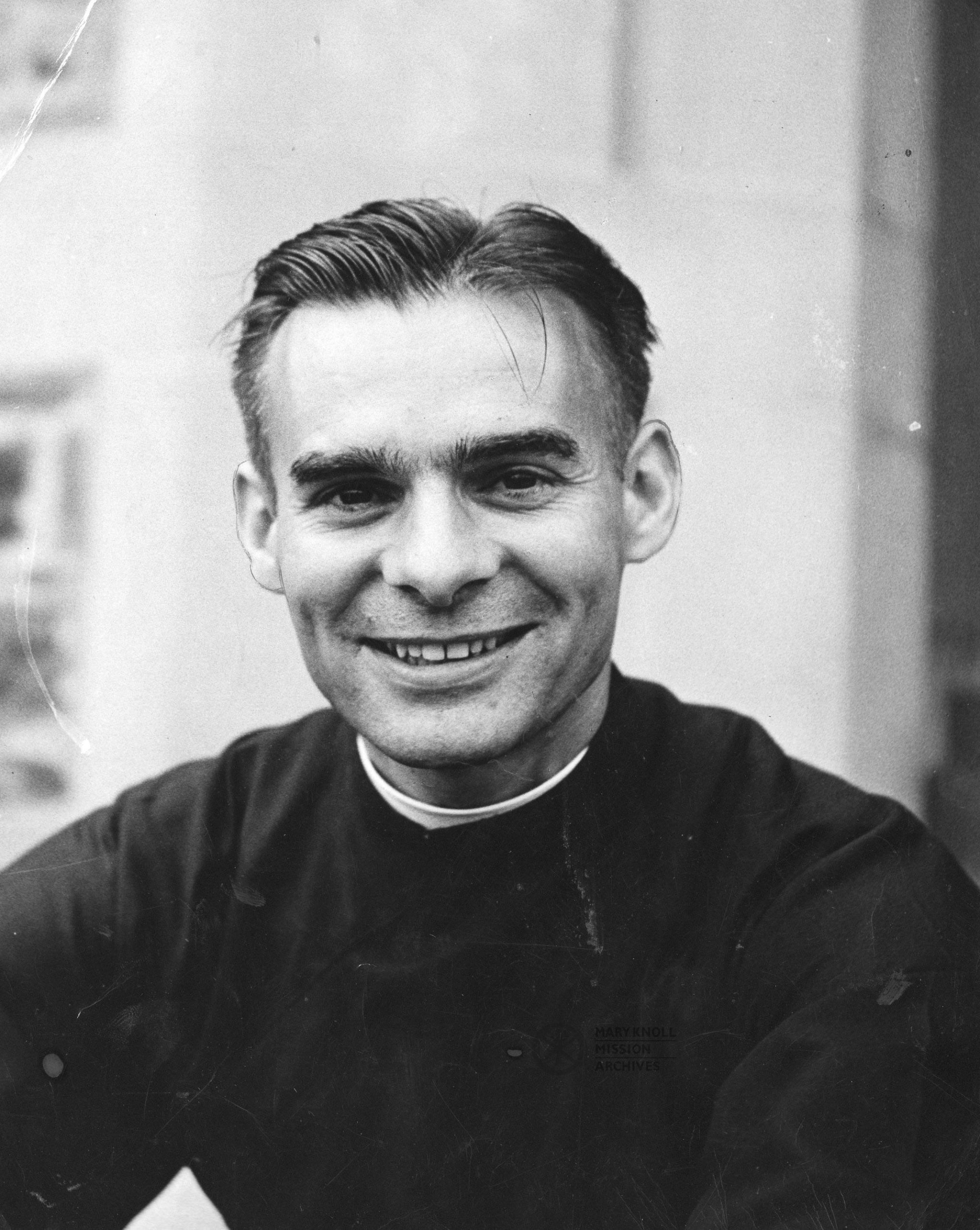

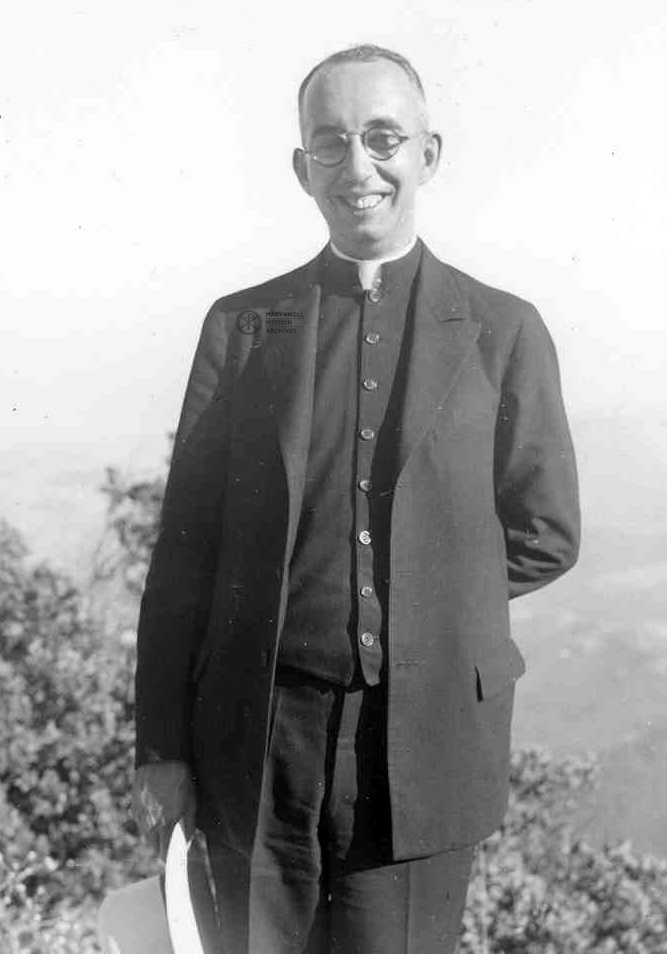

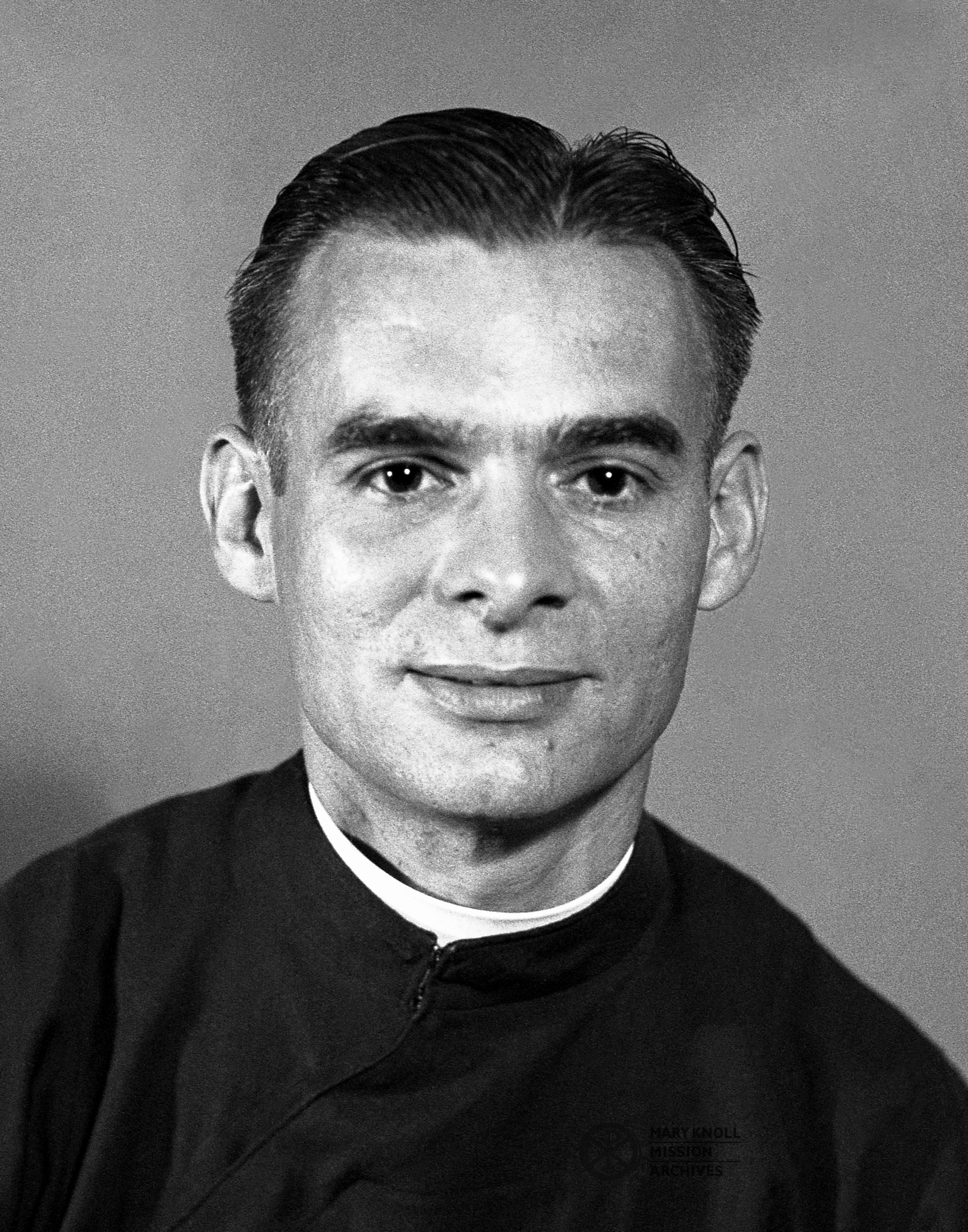

Portrait of Fr. William T. Cummings. He was Charlie’s first contact with Maryknoll, and his encouragement helped Charlie to become a Maryknoll Brother.

Spiritual Growth in San Francisco

Things finally took a positive turn again for Charlie at the hospital. It’s noted in Something for God that Charlie’s “desire to help the poor and the sick” brought him to the San Francisco City and County Hospital looking for work. Charlie was devoted to his patients, primarily working in the tuberculosis ward. He frequently assisted patients suffering with alcohol use disorder as the Great Depression continued. Helping patients detox, cleaning up vomit, and offering compassionate care without judgement became another part of his daily routines.

The hospital’s chapel allowed him to reconnect with his Catholic roots and attend daily Mass. He befriended Father Stern, the Jesuit chaplain assigned to the hospital. Together they determined that Charlie had a vocation and would be best suited to join Maryknoll as a missionary Brother. Father Stern brought Charlie to the Maryknoll House in San Francisco and introduced him to Fr. William T. Cummings. Fr. Cummings agreed with Fr. Stern’s assessment, and his support convinced Charlie to fill out Maryknoll’s application that day.

On August 5, 1934, Charlie received a letter welcoming him to join Maryknoll as a Postulant Brother. Unfortunately, his family was not as enthusiastic about his aspirations. They didn’t understand why he wanted to become a missionary Brother and tried to persuade him against it. Despite their concerns, Charlie entered Maryknoll in October 1934 through the Venard Seminary in Clark’s Summit, PA.

Coming to Maryknoll

During a postulancy program, individuals are constantly assessed to determine their aptitude and suitability. This is especially important for potential missionaries, as they will require strength and mental fortitude to accompany the poor and marginalized in their suffering. Bro. Brendan McGillicuddy was assigned as Charlie’s mentor during this process.

No stranger to hard work, Charlie embraced his opportunity to grow spiritually, mentally, and physically. Manual labor was part of the Brothers’ daily routine, and Charlie did not shirk his duty. His superiors noted that he was a “pious, good worker, well liked and recommended by the faculty and the Brothers” (Lyons). In September 1935, he was approved to become a Novice by Bp. James A. Walsh. On October 17, 1936, Charlie took his First Oath to the Society and officially became Bro. Gonzaga. He took his Perpetual Oath on September 29, 1942.

Labor of Love

Bro. Gonzaga’s first assignment was to the Venard Seminary. While he longed to be chosen for mission overseas, he began to question his path forward. He contemplated becoming a cloistered religious, and could not shake the idea. In January 1938, Bp. James A. Walsh allowed him to leave Maryknoll and live with the Trappist community in Gethsemani, KY. Bro. Gonzaga returned to Maryknoll in April 1938, resolved that God was calling him to serve the missions.

Over the next several years, he relocated between the Venard, the Center House in Maryknoll, and the Society House in Akron, OH. Hard working Bro. Gonzaga could be found wherever his skills were most needed. He dedicated himself to the Blessed Mother, deepening his spiritual practice, and serving others. In 1945, Brother was finally selected to serve in mission in the Pando Vicariate, Bolivia.

He was generous to the point of great self-sacrifice and gave freely of whatever he had.

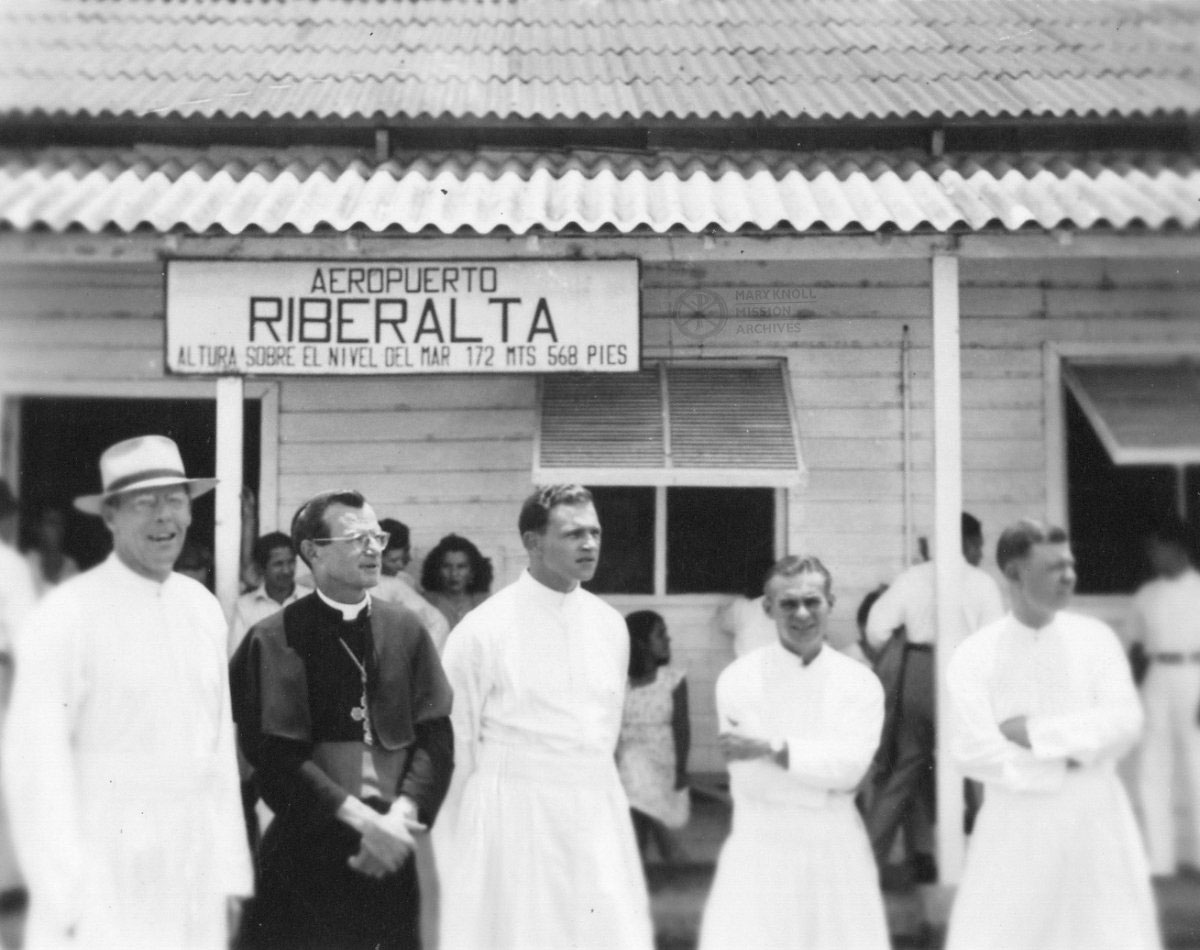

(Left to right) Fr. John B. Gallagher, Bp. Thomas Danehy, Fr. Michael Rick, Bro. Gonzaga Chilutti, and Fr. Bernard Garrity at the Riberalta Airport.

Are we there yet?

The Pando Vicariate spans the northern-most region of Bolivia and is firmly situated within the Amazon Rainforest. Most of this region is currently a National Wildlife Reserve, established by the Bolivian government to preserve the rich diversity of life found under the forest’s canopy. Indigenous peoples, whose families have lived in the Amazon for generations, have continued to fight against deforestation and destruction of their ancestral homes. In 1945, the easiest way into this lush tropical forest was through the Riberalta Airport.

Getting from Maryknoll, NY to Riberalta, Bolivia was no small undertaking in the 1940’s. It involved several increasingly smaller planes with multiple layovers, a train ride, a steam ship, and a couple of taxis.

“His route took him first from New York to Miami, thence to Cali, Columbia, and from there Lima, Peru, and on to Arequipa in the same country. Then he would take the train up over the Andes to Puno, on Lake Titicaca, where he would shift to steamer and cross into La Paz, Bolivia. From there it was a short hop by plane to Cochabamba and then another three hours of flight to Riberalta.” (Lyons)

Thankfully, Bro. Gonzaga was not alone on his harrowing journey. Fr. William Moeschler was his faithful traveling companion through the good (Bro. Gonzaga’s first airplane ride!), the bad (experiencing airplane sickness for the first time) and the ugly (losing part of his luggage in La Paz). The last leg of the journey to Riberalta was shared with Fr. Thomas Danehy, riding in a cargo plane full of rice, sugar, and kerosene. When the plane entered a storm, it started raining on them from a crack in the ceiling! Despite Bro. Gonzaga’s fears, the plane landed safely in Riberalta.

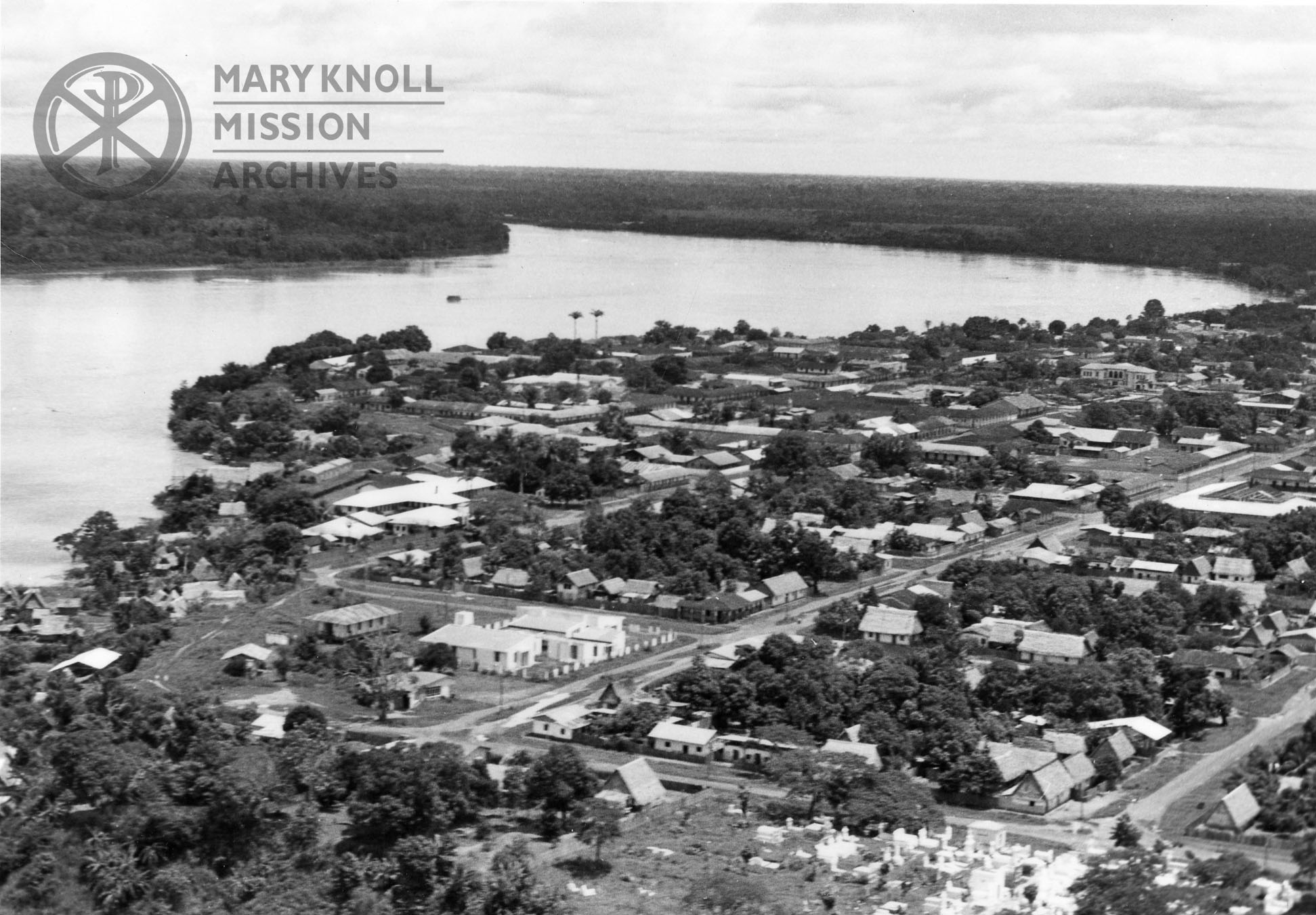

Riberalta and the Beni River

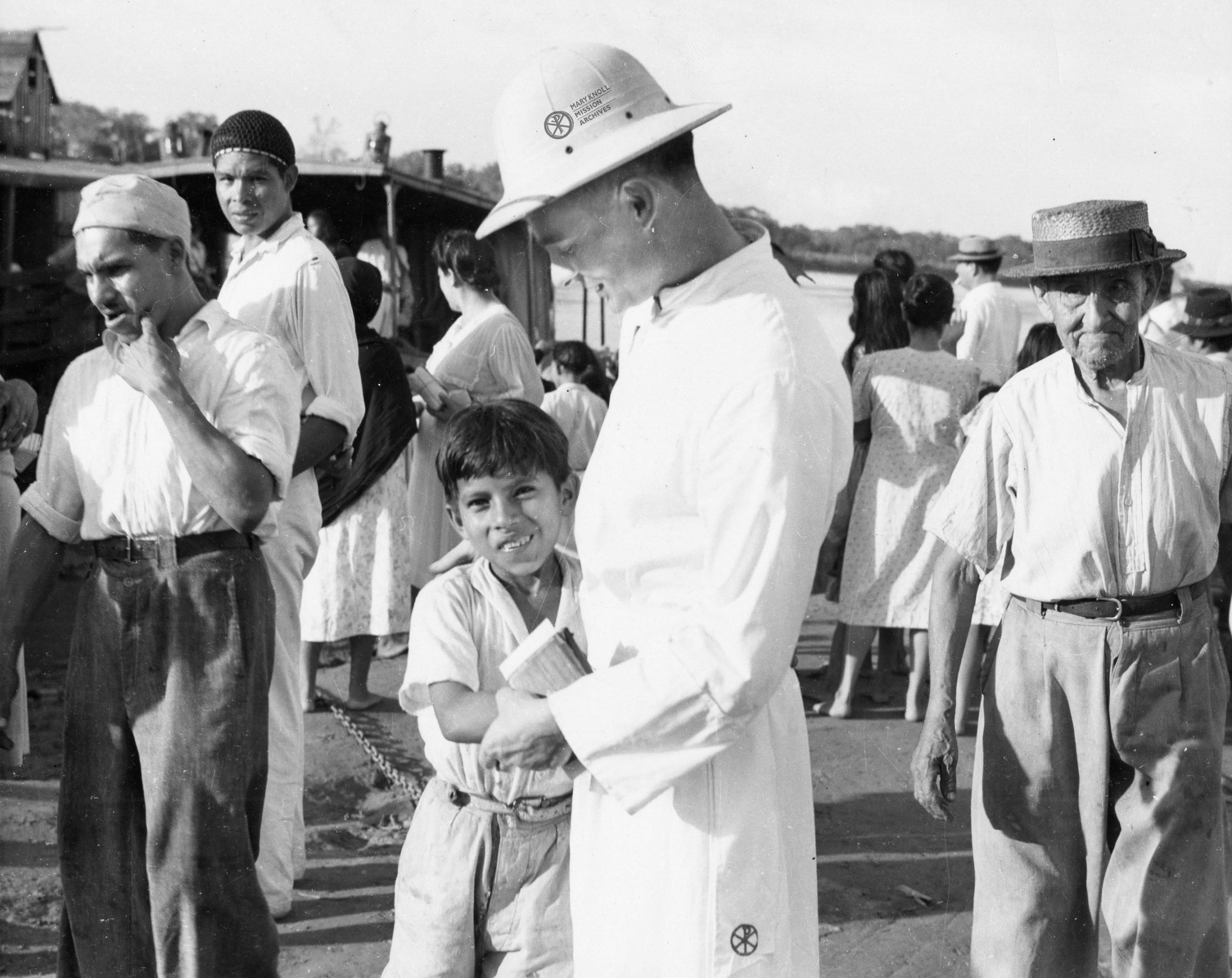

Riberalta served as mission central for Maryknollers assigned to the Pando Vicariate. While stationed here, Bro. Gonzaga took Spanish classes, rebuilt broken motors, and in his spare time helped Fr. James McCloskey teach Riberalta’s Catholic children. The local boys looked up to Bro. Gonzaga as an older brother, and followed him whenever they could. He was affectionately known as “Hermanito” by everyone in town.

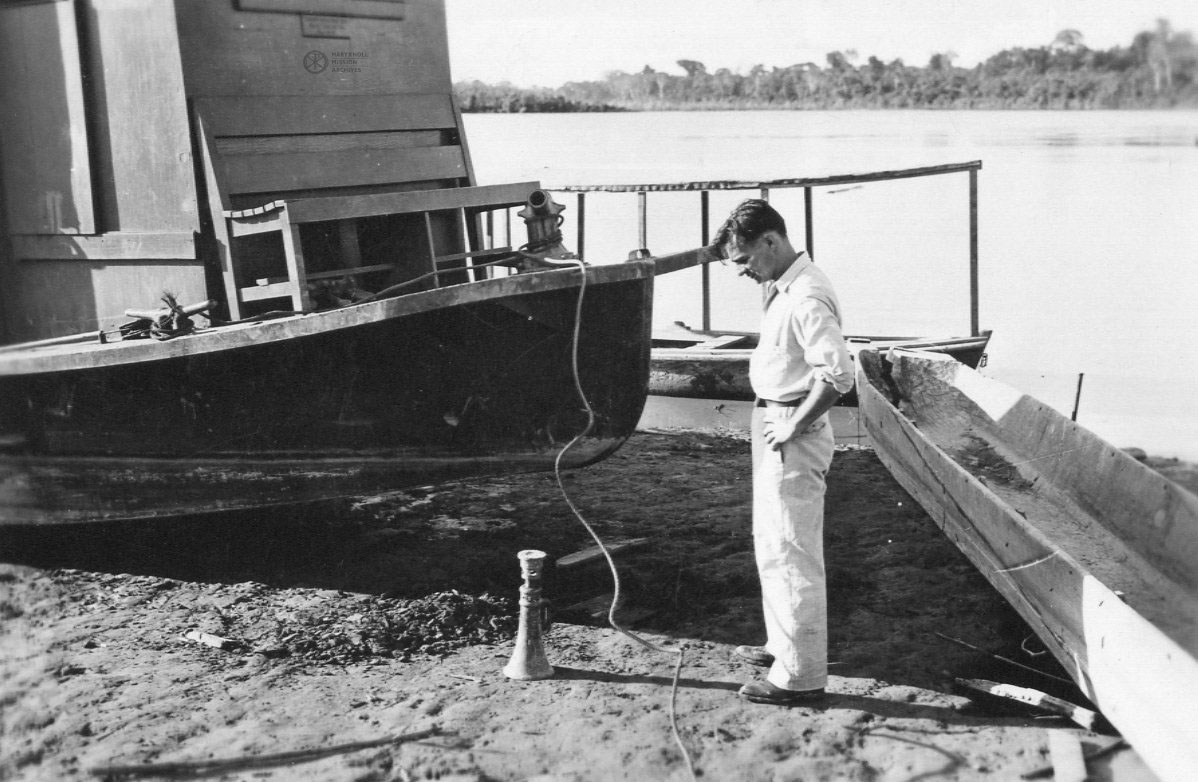

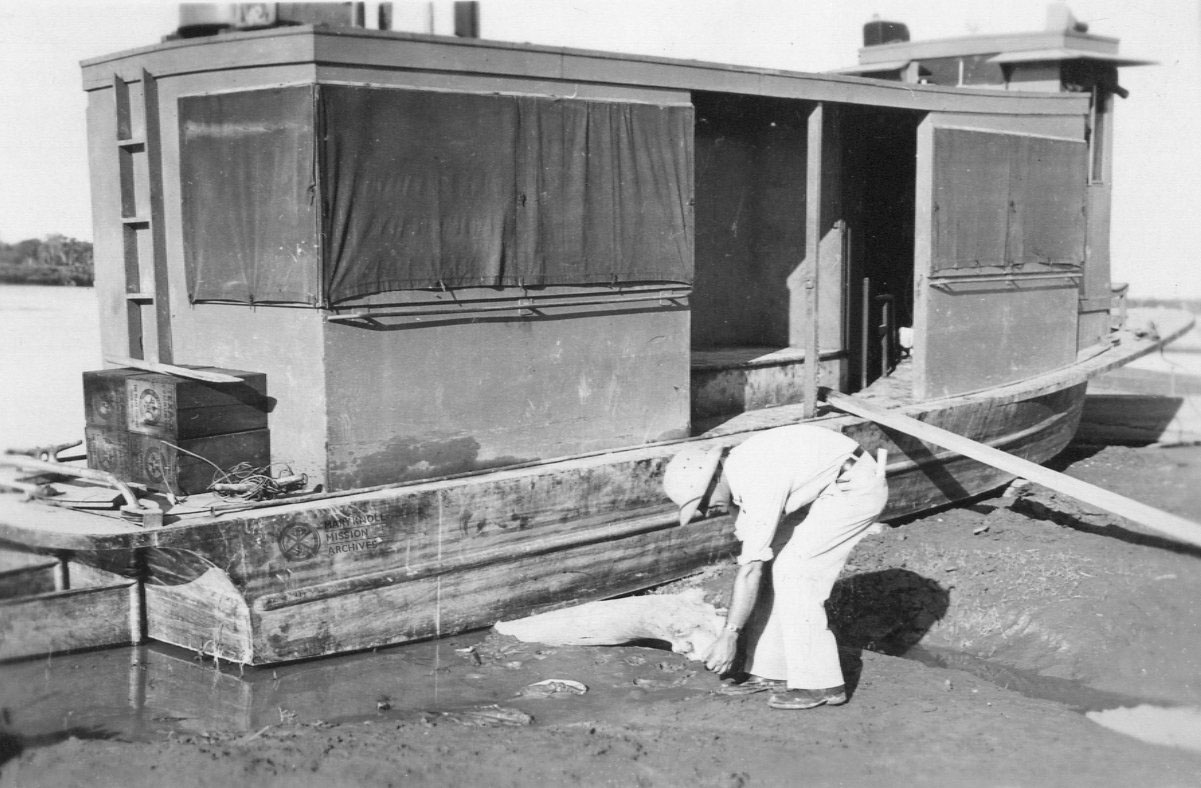

Most of his seven years in mission, however, were spent sailing the Beni River aboard the good ship Innisfail. The Innisfail served valiantly by carrying critical supplies up and down the river to remote villages and isolated families living along its banks. Subsistence farming and hunting were common practice here and every little bit counted towards survival. Maryknollers brought textiles, medicine, local news, and compassion to everyone they encountered.

Unfortunately for Bro. Gonzaga, the Beni was not kind to the Innisfail. Silt and sediment from the river bed often got into the engine, causing serious failures until it could be cleaned out. The river was full of branches and fallen trees, hidden by its cloudy surface, and even the most skilled pilot could run aground or damage the boat by accident.

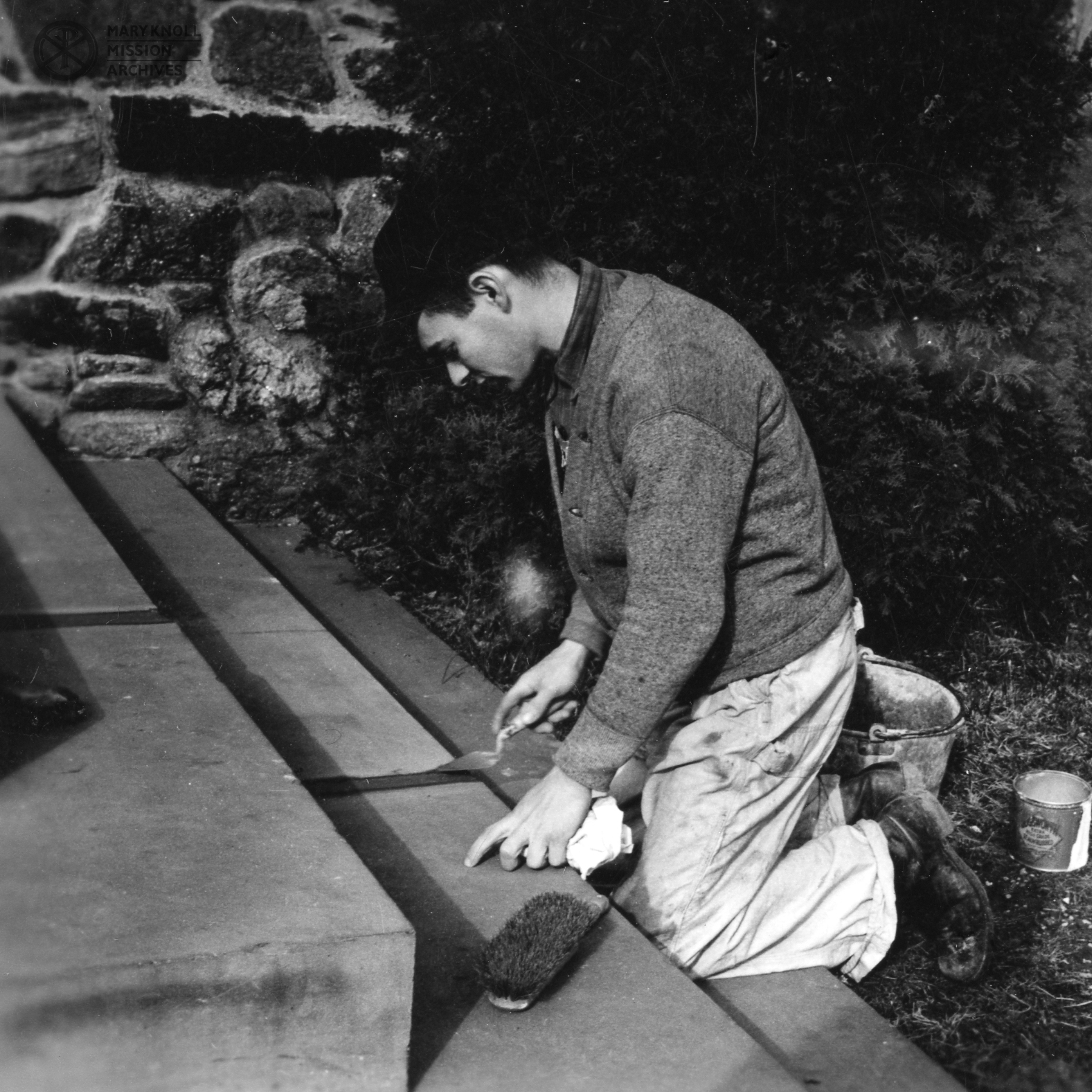

Brother‘s mechanical skills and patience served the mission well. The Innisfail provided the fastest, most efficient way for Maryknollers to bring supplies to the poor and the sick, even with its constant need for repairs. Despite how repetitive the job was for Bro. Gonzaga, he diligently continued to build and rebuild the Innisfail’s engine.

Caviñas

When Bro. Gonzaga wasn’t in Riberalta or traveling the Beni River, he supported Fr. Gordon Fritz at his agricultural mission in Caviñas. A good mechanic was always needed to maintain and fix farming equipment. Just like the Innisfail, the mission’s tractor engine was frequently pulled apart and rebuilt under Bro. Gonazaga’s tender ministrations. Fr. Fritz’s tractor was a critical asset for transporting rubber harvests from 75 miles into the forest and back out to the river ports for sale. All profits from the rubber sales were used to purchase necessities such as general goods, food, and building supplies to improve the lives of Father’s parishioners.

(Back row) Fr, Michael Ruck and Bro. Gonzaga Chilutti. (Front row) Fr. John B. Gallagher and Bp. Thomas Danehy. Photo taken in the Pando Vicariate, Bolivia, 1951.

Circumstances Change

For seven years, Brother labored alongside his fellow Maryknollers to improve the lives of people in need. He integrated into the community, made friends, and became a leader by example. Bro. Gonzaga’s dedication to his work never wavered, however, he began to experience difficulties with his health.

When Brother first arrived at Riberalta in 1945, he was 32 years old and in relatively good health. As time went on, however, Bro. Gonzaga began experiencing stomach pains that slowly grew in intensity. He was hospitalized and put on bed rest. Once the pain subsided, he would go back to work, only for his stomach troubles to begin again. His increasing health concerns were reported back to the General Council at Maryknoll, and it was decided that Bro. Gonzaga would return to the United States for an extended leave.

One Last Boat Ride

Bp. Raymond Lane, Superior General, personally delivered that news to Bro. Gonzaga in January 1952 while on visitation to Bolivia. Brother was reluctant to leave the mission, but was assured that once his health stabilized every effort would be made to return him to the Pando Vicariate and the people he loved. In the meantime, Bro. Gonzaga would escort Bp. Lane on one last trip up and down the Beni River before he left.

Their journey downriver from Riberalta began well enough. The party included Bp. Lane, Bp. Thomas Danehy, Fr. Bonner, Fr. Thomas Higgins, Bro. Gonzaga, and Ignacio, a local chef. Together, they introduced Bp. Lane to the communities they served, their labors of love, and life along the Beni River. When Bro. Gonzaga wasn’t monitoring the Innisfail’s engine, he could be found praying over it, gently requesting it not break down and allow the party smooth sailing.

To Brother’s credit, the engine did not give out on them during their journey. It continued to run smoothly thanks to his diligent care. During the evening on February 11th, a rotting tree fell on the Innisfail, damaging the engine and effectively grounding the boat. Everyone was scared but unharmed, except for Bro. Gonzaga who had been praying over the engine like usual. He was instantly knocked unconscious by the tree. Brother never regained consciousness and died within the hour.

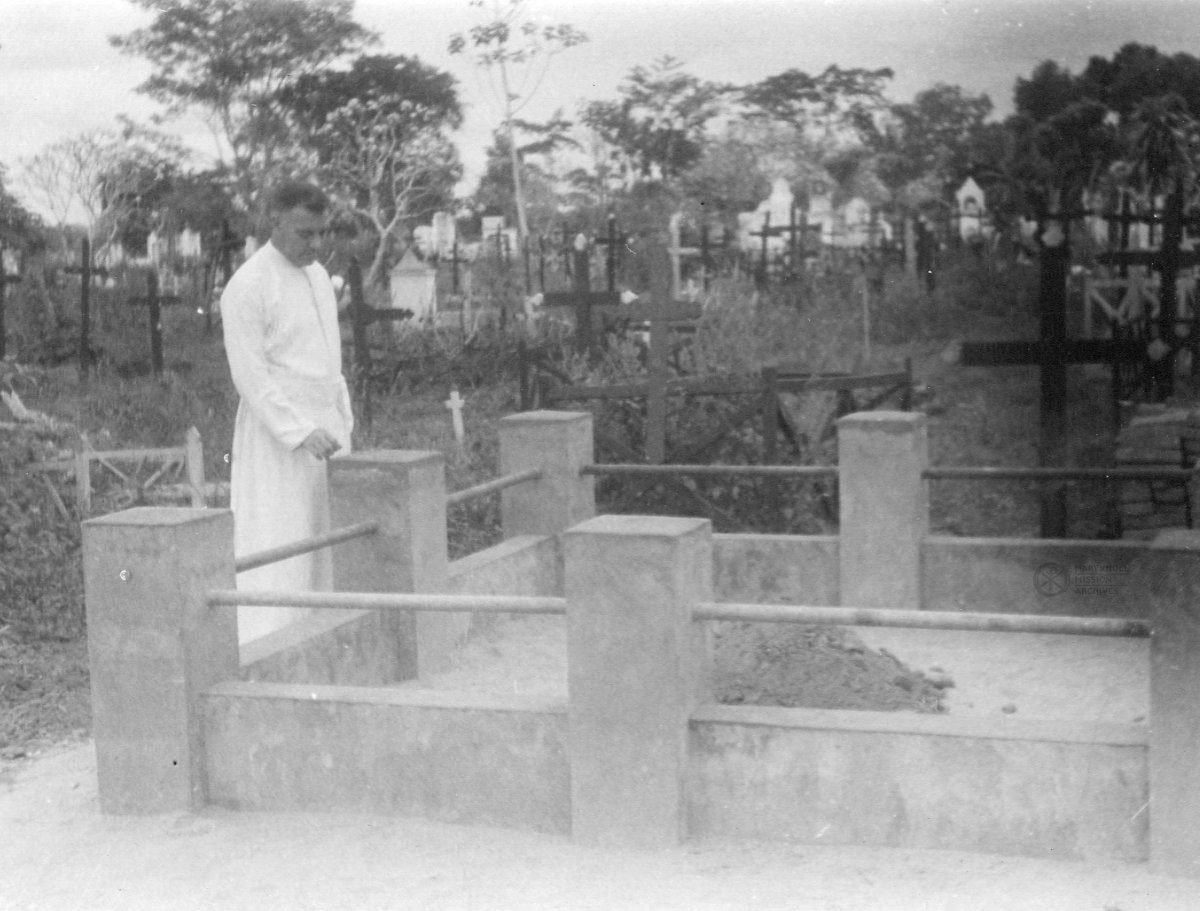

Fr. Bonner visiting Bro. Gonzaga Chilutti’s final resting place in Riberalta Cemetery, Riberalta, Bolivia. c. 1950s-1960s.

Prayers for the Dead

On February 12th, Bro. Gonzaga’s body was laid in state at the nearby mission chapel of Ethea. Members of the community kept a solemn vigil for his soul throughout the night. The following day, Bp. Lane celebrated a Requiem Mass, Fr. Bonner preached his funeral service, and Brother’s remains were buried temporarily in Ethea. Later they were moved upriver and reinterred in Blanca Flor. Eventually, Bro. Gonzaga’s remains were returned to Riberalta, where they were laid to final rest.

A full report of Bro. Gonzaga’s tragic death was published in the October 1952 edition of the Maryknoll Magazine. He is counted among the many devoted missioners throughout history who gave their suffering to God for the edification of others. Despite the hardships of his youth and adulthood, he endured without losing his inner light and compassion for others. We could all learn from his example of strength, patience, and faith in the face of adversity.

Interested in learning more about Maryknoll? You can contact the Archives at:

Maryknoll Mission Archives

PO Box 305, Maryknoll, New York 10545

Phone: 914-941-7636

Office hours: 8:30 am-4:00 pm Monday-Friday

Email: archives@maryknoll.org

Website: www.maryknollmissionarchives.org

References:

Bishop James A. Walsh. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2019, July 25). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/bishop-james-a-walsh/

Bishop Raymond A. Lane, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2014, April 22). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-fathers-bro/bishop-raymond-a-lane-mm/

Bishop Thomas J. Danehy, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2020, December 1). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-fathers-bro/bishop-thomas-j-danehy-mm/

Brother Brendan McGillicuddy, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2014, April 22). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-fathers-bro/brother-brendan-mcgillicuddy-mm/

Brother Gonzaga Chilutti, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2014, April 17). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-fathers-bro/brother-gonzaga-chilutti-mm/

Cairns, M. (2023, March 27). Fr. Thomas A. Barry – life and legacy in Japan. Maryknoll Mission Archives. https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/fr-thomas-a-barry-life-and-legacy-in-japan/

Cairns, M. (2023, July 19). Maryknoll memoirs: Fr. John J. Massoth. Maryknoll Mission Archives. https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/maryknoll-memoirs-fr-john-j-massoth/

Cairns, M. (2024, March 6). Maryknoll Memoirs: Sr. Marianna Akashi. Maryknoll Mission Archives. https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/maryknoll-memoirs-sr-marianna-akashi/

Caldwell, H. (2022, March 1). Orphanages and Orphans. Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/orphanages-and-orphans/

Deceased fathers and brothers. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2019, July 22). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-fathers-and-brothers/

Father Gorden N. Fritz, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2022, December 20). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-fathers-bro/father-gordon-n-fritz-mm/

Father James V. McCloskey, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2014, April 22). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-fathers-bro/father-james-v-mccloskey-mm/

Father Thomas A. Barry, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2014, April 16). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-fathers-bro/father-thomas-a-barry-mm/

Father Thomas C. Higgins, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2014, April 22). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-fathers-bro/father-thomas-c-higgins-mm/

Father William H. Moeschler, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2014, April 23). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-fathers-bro/father-william-h-moeschler-mm/

Father William T. Cummings, MM. Maryknoll Mission Archives. (2014, April 23). https://maryknollmissionarchives.org/deceased-fathers-bro/father-william-t-cummings-mm/

History – CSS Philadelphia. Catholic Social Services. (2023). https://cssphiladelphia.org/about/history/

Lyons, F. X. (1960). Something for god: The life of maryknoll’s brother Gonzaga. P.J. Kenedy & Sons.

National Archives and Records Administration. (n.d.). The flu pandemic of 1918. National Archives and Records Administration. https://www.archives.gov/news/topics/flu-pandemic-1918

Our history. Sisters of Saint Joseph. (2022). https://ssjphila.org/about-us/our-history/

St. John’s orphan asylum postcards. [graphic]. Library Company of Philadelphia Digital Collections. (n.d.). https://digital.librarycompany.org/islandora/object/digitool%3A97271

Special Assembly of the Synod of Bishops for the Pan-Amazon Region. (2020). The Amazon in Bolivia. Amazonia: New Paths for the Church and for an Integral Ecology. http://secretariat.synod.va/content/sinodoamazonico/en/the-pan-amazonian-region/the-amazon-in-bolivia.html#:~:text=Currently%20in%20the%20territory%20of,%2C%20Movimas%2C%20Moxe%C3%B1os%2C%20Nahuas%2C

Wikimedia Foundation. (2022, July 29). Apostolic Vicariate of Pando. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apostolic_Vicariate_of_Pando

Wikimedia Foundation. (2024, August 29). Great depression. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Depression

Hand drawn portrait of Bro. Gonzaga Chilutti, n.d.

Bp. Thomas Danehy and Bp. Alonso Escalante cruise on the Beni River, Riberalta, Bolivia, 1942.

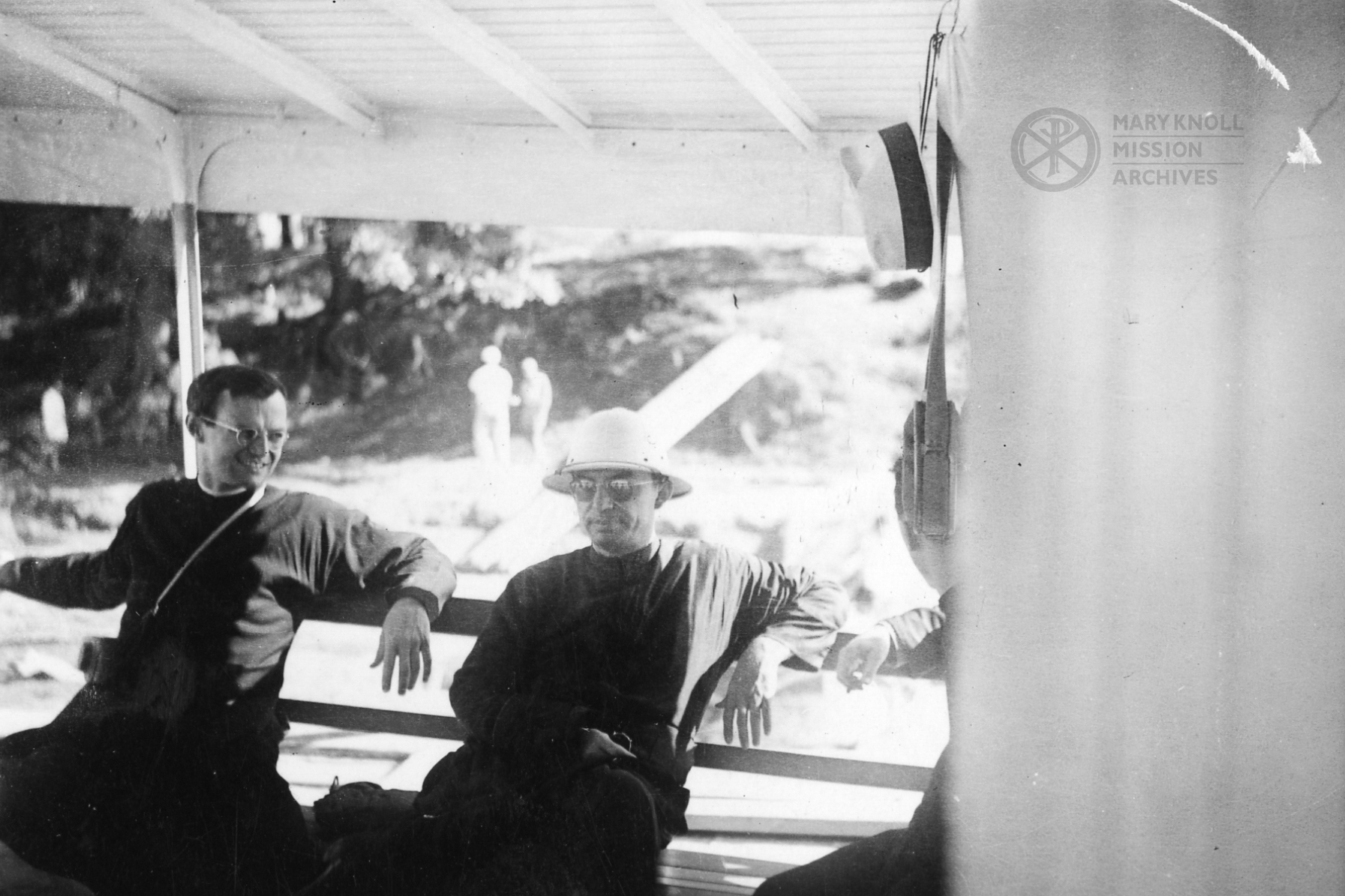

Maryknoll Fathers stand aboard a boat on the Beni River near Riberalta, Bolivia.

Aerial view of Riberalta, Bolivia. Part of the Beni River can also be seen.